The current “Women’s Revolution” in wrestling appears to be anything but revolutionary. Women wrestlers are finally getting the opportunity to do things they were already doing.

If it seems like they have become more demanding, it is because they have seen how easily it can all be taken away. This is the story of the Ladies Professional Wrestling Association, a blueprint for a revolution.

The first ‘Rocky’ movie hit cinemas nearly fifty years ago. The franchise used to have a knack for launching people into superstardom. Such was the case when Hulk Hogan had a small role in the third installment.

Vince McMahon took advantage of this by making Hogan his top star and announcing that his World Wrestling Federation would specialize in “sports entertainment.”

He tried to make it cool to admit you liked to watch wrestling even if you knew it was scripted.

McMahon demonstrated his vision with the first cross-promotion event of its kind in 1985 called WrestleMania. Lauper played a key role in making it a commercial success. Just before the main event, she was in Wendi Richter’s corner as she defeated Leilani Kai for the WWF Women’s Championship.

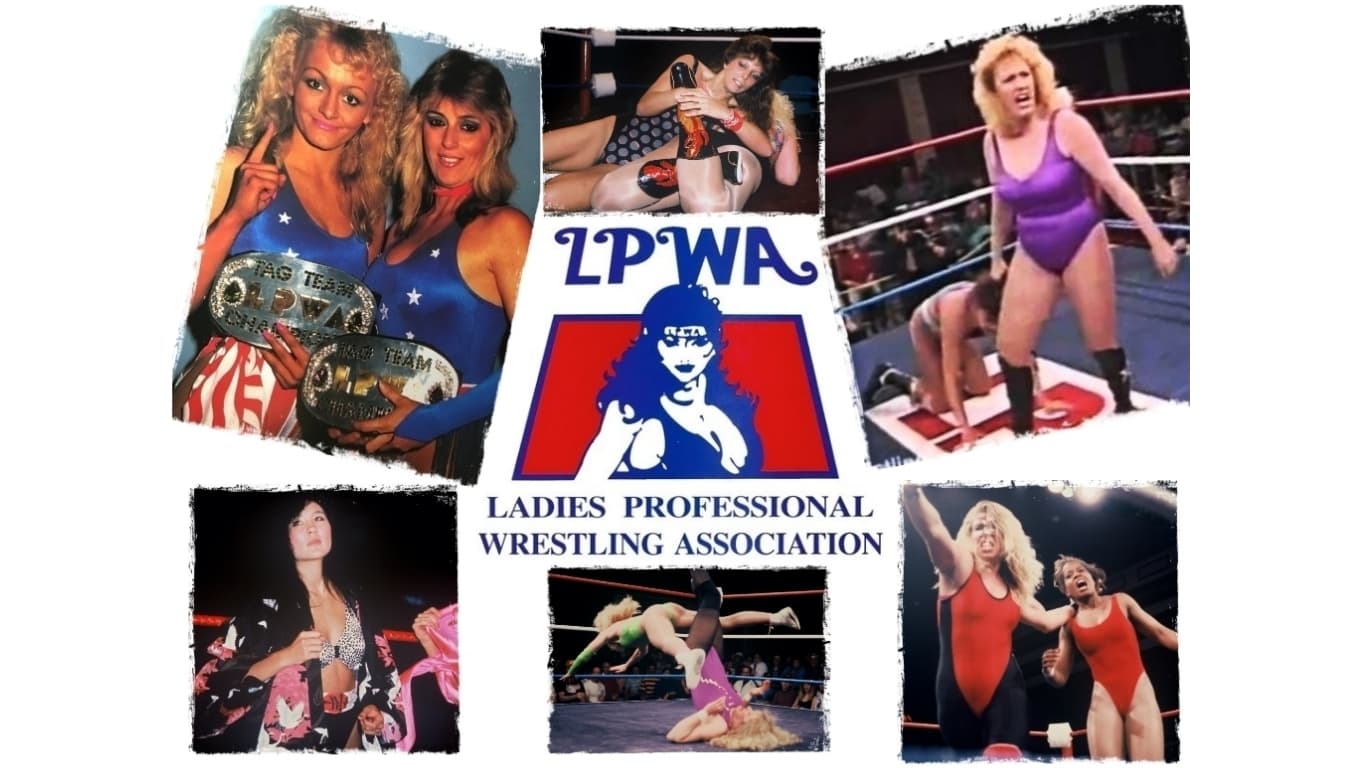

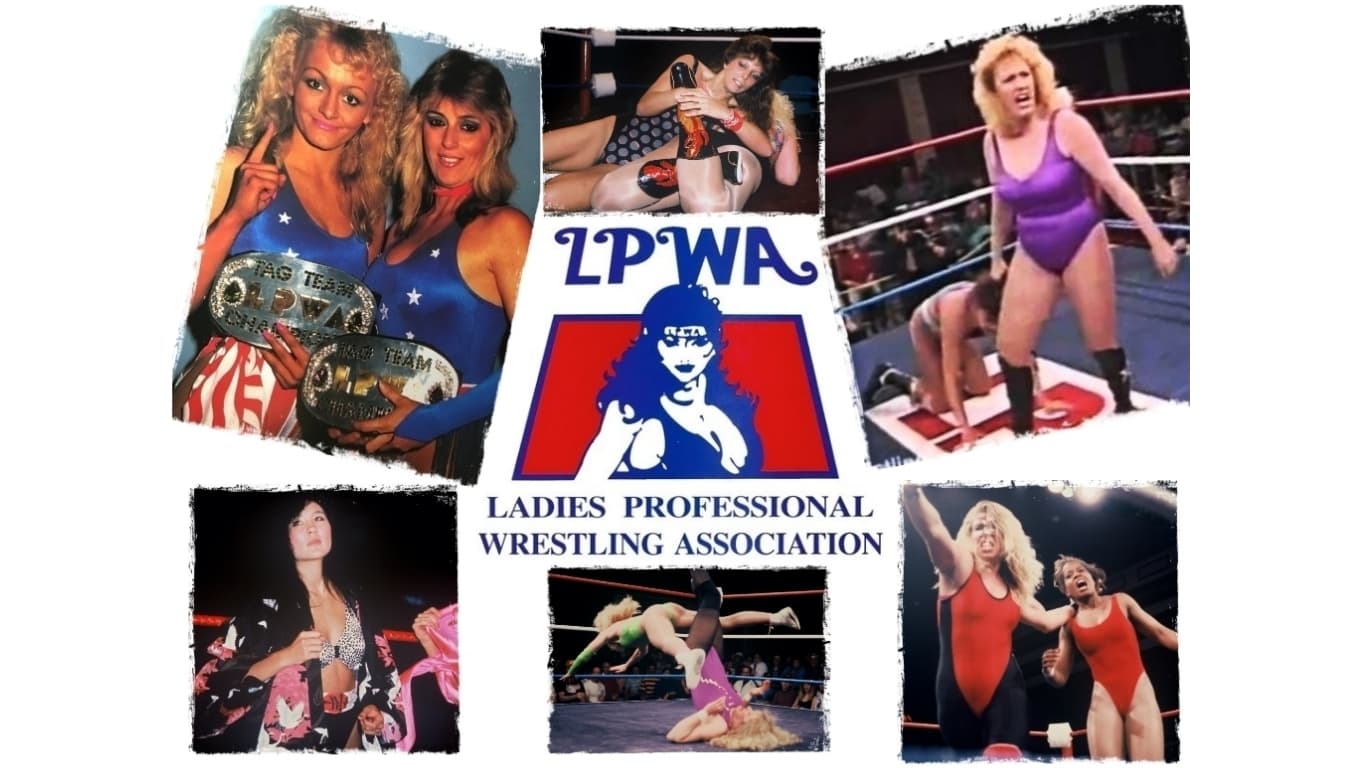

Ladies Professional Wrestling Association

A year later, WrestleMania 2 became a much larger spectacle. The pay-per-view aired lived from three different cities.

The Chicago portion opened with The Fabulous Moolah retaining the title against Velvet McIntyre. Then WrestleMania III became one of the largest events held on American soil.

A rumored 93,000 people witnessed Ricky Steamboat and Randy Savage stealing the show, Adrian Adonis being shaved bald after being squashed by Roddy Piper, and Hogan bodyslamming Andre, the Giant.

But they didn’t see any women competing on the card. Not even one. There would not be another women’s match on WWF’s flagship event until WrestleMania X in 1994.

It would be facetious to claim that any woman back then had the same drawing power as Steamboat, Savage, or Piper. They definitely didn’t rival Hogan. But it would be wrong to suggest that they had the same opportunities to be.

It wasn’t just the WWF that had developed this attitude towards women’s wrestling. Promotions tended to have one or two big names that attracted paying fans.

They were almost always larger men with great physical strength. Any promotion without such a star would bring them in from other companies. Keeping these stars profitable meant feeding them a steady stream of viable competition.

They could be other men on the roster, large guys brought in from other promotions, or just big guys spotted at the gym or working as bouncers.

One place you could not find viable competition was in the women’s locker room.

The Blueprint for a Revolution

With rare exceptions, women wrestlers were visibly too small and light to compete against male heavyweights.

They would always be underdogs, with any victories needing to be rare. Women were at greater risk of injury when they competed against men.

Even if they were willing to take those risks, most athletic commissions strictly forbid it. Booking a woman against a man could result in heavy fines or licenses being revoked.

Then there was the blatant sexism. Some men within the industry refused to believe that fans would pay to see women wrestlers. A minority felt it would ruin their credibility to work with one.

Women were also held to an irrational stigma that they would get take a year out each time they got pregnant and would eventually retire young to be full-time mothers.

“When you’re injured, it’s not that glamourous of a life, let me tell you. But when you get hurt you’ve got to keep going, and I’m a trooper.”

– Magnificent Mimi on the struggles of making it in the wrestling business.

As long as women couldn’t work with the big stars, they weren’t seen as potential money draws. As a result, promoters became less willing to book them. Women had fewer opportunities to impress fans.

As a result, fans expected less from them and became less interested. Promoters saw this and took it as justification for using them less. This vicious circle made it harder for women to make a sustainable income from working matches.

Those who didn’t give up were forced to take better-paid roles as valets, ring girls, or in the office. As a result, women wrestlers did everything but wrestle.

The Blueprint for A Revolution

The final straw happened at WrestleMania V in 1989. Rockin’ Robin opened the show by singing the National Anthem. The reigning Women’s Champion did not have a match on the card. No woman did.

It was only four years since Lauper used her fame to endorse the WWF’s women’s division. Now the highest-ranking woman in the industry was still struggling to get booked on television.

Change was urgently needed.

Ladies Pro Wrestling Association was founded by Tor Berg in 1989. He aggressively sought television deals and wound up making two television series.

‘The Super Ladies of Wrestling’ was an hour-long broadcast, while episodes of ‘Ladies Championship Wrestling’ were thirty minutes.

The shows were filmed mainly in casinos in Laughlin, Nevada, and were broadcast on every sports network across the country. Berg also had episodes compiled into home video releases for further distribution.

The unique thing about this promotion wasn’t the all-female roster. It was how it didn’t aim to be a rival promotion. It was more like a developmental brand.

Their primary purpose was to elevate women’s wrestling. Their shows gave women the platform that the bigger televised promotions would not. Nearly every woman who stepped into the LPWA ring was a free agent.

They were allowed to work for any other company at the same time. In fact, the LPWA helped them to negotiate better deals in bigger promotions. The LPWA had no shortage in trained female talent who were struggling to get booked elsewhere.

Wally Karbo – Commissioner

There was also no shortage of industry insiders who wanted to help out. Berg hired veteran event promoter Wally Karbo as the Commissioner. Karbo worked for the National Wrestling Alliance before founding the American Wrestling Association.

In addition to his vast experience, his connections to the AWA gave them access to more talent. While most companies gave women a maximum time limit of ten minutes, LPWA gave them fifteen and encouraged them to make use of it.

They emphasized the use of holds and grappling and discouraged hair-pulling and scratching. To help enhance their abilities, Olympic wrestler Brad Rheingans was brought in as Head Trainer.

In addition, multi-time NWA World Heavyweight Champion Nick Bockwinkel worked as an announcer and an adviser, as did veteran manager Jim Cornette.

To help the women be taken more seriously, the company avoided gimmick matches (other than battle royals). They refused to do any match type that put emphasis on sexuality or nudity.

LPWA brought in the best female talent from around the world to be both performers and trainers. The LPWA had a varied roster that utilized talents from all over the world.

This included countries that North American promotions usually would not normally feature, including Russia, South Korea, South Africa, and Iraq.

Ladies Professional Wrestling Association – LPWA Championship

The promotion’s main title was simply named the LPWA Championship. It was given to Australian wrestler Susan Sexton. She had relocated to the United States in 1975 to begin her international career.

Sexton had just joined the AWA as the LPWA was being put together. She would defend the LPWA Championship in multiple companies, including the NWA’s Clash of the Champions XII: Fall Brawl ’90 event.

She retained the title for a year before losing it to Lady X. Lady X is better known to fans as Peggy Lee, who competed in both WWF and AWA prior to LPWA.

She also had a year-long run with the title before losing it to Terri Power (WWF’s Tori) at their final event.

“Even friends who were friends with me before I became champion can’t even be with me as they were before because I have different responsibilities.

I have different things I have to do. It causes a gap. It always does when you elevate to a position like being the champion of the LPWA. It’s a very elevated position. It is very hard for the girls to keep up with me.”

– Susan Sexton on how lonely life can be for a titleholder.

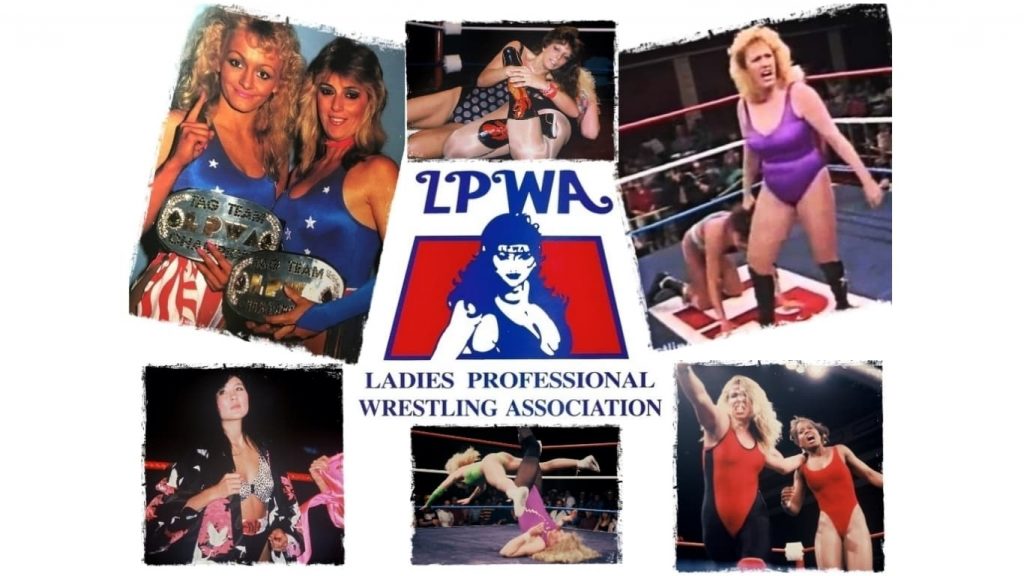

Soon after the company launched, they debuted the LPWA Tag Team Championship. Unlike their main single’s championship, the first holders were decided in a match.

Team America (Heidi Lee Morgan and Misty Blue) defeated a tag team known as “Bad, Black and Beautiful” (Bad Girl and Black Venus). Team America defended the titles against both singles stars and tag teams from around the world.

Their most persistent threats would be the famous Jumping Bomb Angels and The Glamour Girls. It would be the Glamour Girls (Judi Martin and Leilani Kai) that ended Team America’s run with the titles after a year.

The heels, also known as “The Queen’s Court,” would hold the belts until the company closed.

Even though the company’s focus was on women’s wrestling, it did benefit from having established male stars on screen. They mainly served as announcers or managers. Veterans like Bockwinkel, Cornette and Sgt.

Slaughter had roles calling the action from the announcers’ desk. Adnan Al-Kaissie (General Adnan) and Barry Horowitz were managers that sometimes competed in mixed tag matches to help put over their female opponents.

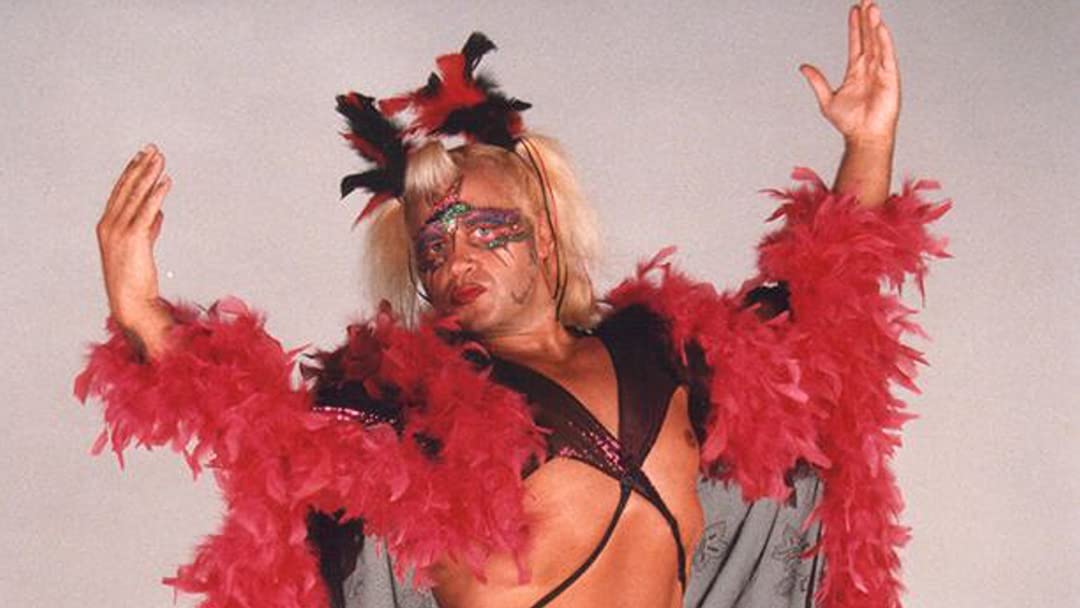

Arguably the biggest male star was “Exotic” Adrian Street. The showman from Wales was a lifelong fan of both British and American pro wrestling. When he started out, the U.K. scene had few unique characters.

Street attempted to stand out with a rock star character that was common in American indie promotions. English fans did not get it and mistook him for a transvestite.

“Exotic” Adrian Street

Once opponents had mistaken him for being weak and effeminate, he would punish them with an unforgiving power-based offense.

He added a new layer to his gimmick by hiring Miss Linda as his valet. Linda accepted the misogynistic abuse she received from street, which only riled fans more.

When they came into LPWA, Linda was now the muscle who competed in the ring, while Street antagonized fans from her corner.

The couple won the World Mixed Tag Team Championship at an LMNW event in Germany in 1973. The pair defended it in every promotion that they visited thereafter. While they were in the LPWA, it was dubbed the “LPWA Mixed Tag Team Championship.”

The title was immediately problematic. By definition, it required men to compete for it as well as women. A promotion that was focused exclusively on women did not intend to build a large men’s roster.

When Street and Linda left LPWA, they took their championship with them. The LPWA never considered having a replacement championship.

Ladies Professional Wrestling Association – The Company Hit a Hard Bump Going Into 1991.

Several of their more reliable stars chose to move on. The lack of information led to many rumors about what was happening behind the scenes. The gossip threatened to taint both of the title changes at the start of the year.

For example, Sherri Martel alleged that Berg had promised Japanese star Noriyo Tateno (of the Jumping Bomb Angels) a permanent job if she retired in her home country and competed in the U.S. exclusively, but then went back on his word.

The allegation made it harder for Berg to do deals with international stars due to their concerns that he would break his deals with them. Berg pushed hard to develop stronger relationships with Japanese promotions.

This resulted in a series of talent exchanges where Japanese stars would use the Ladies Professional Wrestling Association as a gateway into the U.S. scene, and American talent would do tours in Japan.

These changes benefitted stars like Medusa Micelli (Alundra Blayze) and Reggie Bennett. The two adapted well to the mix of styles and impressed fans and opponents in both countries.

“Well, I will tell you this. It’s going to be rough, tough, and not real pretty. And with the Good Lord behind me, I will walk away with the title.”

– Reggie Bennett promo ahead of an LPWA Championship match.

Since the company was founded, Berg had the ambition to host pay-per-view events. He finally achieved this goal in February 1992. LPWA Super Ladies Showdown was built around the tournament for the new LPWA Japanese Championship.

Almost every match on the card featured American talent against Japanese stars. The show took place in Rochester, Minnesota.

Commentary for the event was provided by Bockwinkel and Sue Hennig (the sister of Curt). The U.S. representatives in the tournament were Denise Storm, Susan Green, and Reggie Bennett.

All three had started to create a following in Japan due to their recent work there. Representing Japan were Yukari Osawa, Mizuki Endoh, Eagle Sawai, and Harley and Midori Saito.

The tournament and the title were eventually won by Harley, who defeated Storm in the finals. The show featured five other matches, including one with the woman who was the spark for this concept, Rockin’ Robin.

The high number of matches on the card meant that they had to be shorter than usual. The LPWA’s other titles were also contested. The Glamor Girls retained the tag titles against Bambi and Malia Hosaka.

Ladies Professional Wrestling Association

The main event saw Terri Power capture the main championship from Lady X. This is the story of the first-ever all-woman wrestling PPV held in America more than a decade before WWE held their “first-ever”.

You may recall that we said Power won the Ladies Wrestling Professional Association Championship at their final event. The PPV was considered a commercial failure, and the company closed down soon thereafter.

All of their taped shows continued to air internationally for several more years due to their licensing deals. Just as they were starting to expire, Berg tried to relaunch the promotion with another pay-per-view.

He secured several names for the event, but it never came to fruition. He sold the company and all assets in 2001. The new owner, known as “LPWA, Inc.” continues to negotiate licensing deals for the footage with international networks.

They have also given rights to the website AllWomenWrestling.com to stream over 200 hours of original footage.

A company that only lasted two years may seem like a failure. But in reality, the LPWA achieved what it had set out to do. The death of the company led to a rebirth in women’s wrestling.

Larger companies began to take it seriously once more and featured women prominently on their shows. The WWF reinstated their women’s division, building it largely around LPWA alumni.

Madusa Miceli, competing as “Alundra Blayze” defended the WWF Women’s Championship at WrestleMania against Kai. There has been a women’s match at almost every WrestleMania since.

“When I punish them, I teach them a lesson. […] Believe it. Before long, [future opponents] will be taught a lesson, and they will call me ‘Sensei’.”

– Madusa Micelli promo on her heel tactics.

Stars like Candi Devine, Sweet Brown Sugar (Jacqueline Moore), Terri Power, Tina Moretti (Ivory), and Judy Martin continued to compete in major U.S. promotions for years to come. Others like Reggie Bennett relocated to Japan and had fruitful careers for the next decade.

As a result, at least two dozen alumni are now recognized in various wrestling Halls of Fame, including the WWE. It also inspired several other women-only promotions, including Glorious Ladies of Wrestling, to today’s Shimmer Women Athletes.