On February 11th, 1984, Tito Santana and Don Muraco met at the Boston Garden in a WWF Intercontinental title match that quietly reset the direction of the company’s mid‑card.

It was not a stadium show or a pay‑per‑view. It was a house show in front of roughly 14,500 fans, and the finish didn’t even make TV at the time.

Yet the result elevated Santana, shifted Muraco’s role, and defined how the Intercontinental Championship would be used for the next few years.

Tito Santana and Don Muraco – Setting and Stakes

By early 1984, Don Muraco was deep into his second run as Intercontinental Champion. He’d regained the title from Pedro Morales in January 1983 and spent the next year as a traveling champion, defending against babyfaces like Jimmy Snuka and Tito Santana across the WWF circuit.

Muraco’s heel work was built on smug promos, stalling, and sudden bursts of offense, usually involving a foreign object or some other shortcut.

Tito Santana, by contrast, had returned to the WWF in 1983 as a steady, athletic babyface with credibility from earlier runs and from time in territories like Georgia.

Over the second half of 1983, he was positioned as the next serious challenger to Muraco’s dominance, wrestling him repeatedly and often getting close without sealing the deal.

The Boston audience on February 11th had already seen them clash before; on a previous Boston card, Santana had beaten Muraco by count‑out, giving fans a taste of what a title change might feel like

The Intercontinental Championship itself still had the reputation of being the “workhorse” belt. In the early 1980s, it was usually held by strong in‑ring performers who could carry long matches underneath the WWF World title programs.

For Santana, a win would be career‑defining. For Muraco, another successful defense would underline his status as the promotion’s top featured heel outside the world title picture.

How the Match Played Out

The match in Boston reportedly went just over twelve minutes. The structure was typical for the time but efficient.

Muraco used his size and brawling to control large stretches, slowing the pace with holds, jawing with fans, and teasing exits through the ropes or out of the ring.

Santana relied on speed and timing—arm drags, dropkicks, and quick roll‑ups—to keep Muraco off balance and to create the sense that one well‑timed move could turn the match.

Accounts of the bout and the available footage clips indicate that Muraco targeted Santana’s midsection and back, leaning on chinlocks and clubbing forearms to set up the Hawaiian Hammer and other power spots.

Santana’s comebacks were short but sharp: quick punches, a backdrop, and a few near falls that drew loud reactions from the Boston crowd, which had already embraced him as a rising star.

The key to the match was how the finish was built. Rather than going straight from a big move into a pin, the final sequence emphasized positioning and counters.

Muraco, confident and slightly frustrated, went for a running tackle—something you would expect a bigger heel to use to cut off a rally.

Santana stepped aside at the last second and caught him with a sunset flip as Muraco’s momentum carried him over. The pinfall looked sudden rather than fluky, but it didn’t rely on a knockout strike or a distraction.

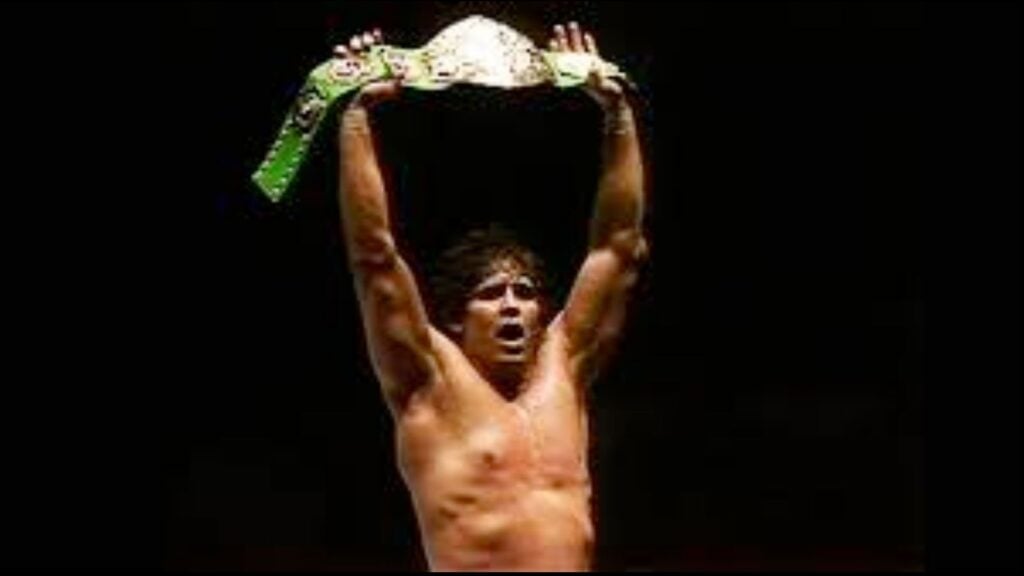

The official time, as recorded in multiple historical listings, is 12:30, with Santana scoring the three count and winning the Intercontinental Championship.

Muraco lost clean, in the middle of the ring, with no foreign object and no outside interference, which was notable given his reputation for cheating to retain.

The “Lost” Title Change

One unusual wrinkle in this match is its lack of full televised footage. Historical summaries of the Boston card note that, while the result is documented, “footage of the finish was lost/destroyed,” and later commentary projects that Santana himself explained how the sunset flip ending came about. That has given the match a bit of a cult status among fans interested in oddities from the pre‑pay‑per‑view era.

Santana has spoken in interviews about how important the Boston Garden win was to him, not just as a title victory but as a moment of validation.

In a discussion about the “lost” Intercontinental title switch, he described the finish and the building’s reaction, saying that he believed the company trusted him as a champion because crowds like Boston’s consistently responded to his work and persona.

While those comments focus more on the memory than on specific spots, they underline how he viewed that night as a turning point.

From Muraco’s side, later retrospectives tend to highlight his year‑plus reign and the caliber of challengers rather than this particular loss.

Nevertheless, the clean pinfall in Boston is usually presented as the capstone to a strong heel run, with Santana cast as the man finally able to overcome Muraco, where others had fallen short.

Who Won, Who Lost, and How It Looked

On paper, the result is simple: Tito Santana pinned Don Muraco to win the WWF Intercontinental Championship, ending Muraco’s reign and starting his own 226‑day run with the belt.

Santana thus became the first Mexican‑American wrestler to hold the Intercontinental title, a fact later noted in career profiles and Hall of Fame discussions.

From an in‑ring standpoint, the match is fairly straightforward. Santana plays the undersized, skilled babyface fighting from underneath.

Muraco, as champion, controls most of the tempo with grinding offense and the occasional big bump or near fall to keep things interesting.

The finish rewards Santana’s persistence and timing rather than sheer power. There are no obvious referee controversies, no outside run‑ins, and no post‑match brawl. The story told is that Santana outwrestled Muraco in the closing seconds.

In that sense, Santana is the clear winner both in kayfabe and in perception. He earns a clean, decisive victory that positions him as a credible secondary champion.

Muraco, meanwhile, loses without excuses, for a heel who had held the title twice and survived brutal feuds with Morales and Snuka, dropping the belt cleanly communicates that his time at the top of the Intercontinental division is over, at least for this chapter.

Short‑Term Impact on Both Careers

In the months immediately following February 11th, the Boston Garden win reshaped Santana’s role in the WWF. His first reign lasted from February 11th until September 24th, 1984, when he dropped the title to Greg “The Hammer” Valentine in London, Ontario.

That 226‑day stretch saw him defend regularly on house shows and featured programs, presenting him as a fighting champion in line with the Intercontinental belt’s workhorse image.

This title run also set the stage for his long feud with Valentine, which many historians regard as one of the defining rivalries in the history of the championship, culminating in their cage match rematch in 1985.

Without the earlier win over Muraco, Santana would not have entered that program with the same established aura as a former champion, and the stakes would have felt lower.

For Muraco, losing the belt to Santana did not end his relevance, but it did mark the end of his time as the primary Intercontinental focal point.

After dropping the title, he moved into other feuds and later reunited with manager Mr. Fuji for tag team runs and mid‑card programs, eventually shifting down the card as newer heels emerged.

By the time the national expansion and WrestleMania era kicked into full gear, Muraco was still visible, but the Intercontinental spotlight had moved on.

Long‑Term Significance

Looking back, the February 11th, 1984 match matters less for its move set and more for its placement in the broader WWF timeline.

It occurred just as Vince McMahon Jr. was pushing the company into full national expansion and about a year before the first WrestleMania.

Establishing reliable, athletic babyfaces who could hold up the middle of the card was crucial, and Santana fit that role perfectly.

Becoming the first Mexican‑American Intercontinental Champion also strengthened Santana’s connection with Latino fans and added a layer of representation that has been noted in later write‑ups about his career.

The Boston win provided the factual foundation for that legacy, and his subsequent reign, with defenses against Muraco and others, made it more than a trivia note.

For Muraco, the match is part of the arc that shows his versatility. He had already beaten Pedro Morales twice for the same belt, including in a Texas Death Match, and had headlined major arenas as a hated champion.

Losing to Santana cleanly in Boston underscored that he could do the honors for a rising babyface in a key market, something a reliable heel needs to be able to do to extend his usefulness over time.

In the End…

The February 11th, 1984 Intercontinental title match between Tito Santana and Don Muraco at the Boston Garden was not a spectacle loaded with gimmicks or historical video packages.

It was a twelve‑minute house show title switch built on simple, clear storytelling: a dominant heel champion, a determined babyface challenger, and a clean, well‑timed finish that rewarded persistence and timing.

Tito Santana walked away with the belt, beginning a 226‑day reign and becoming the first Mexican‑American Intercontinental Champion, a milestone often cited in later profiles of his career.

Muraco, after more than a year on top of the Intercontinental division, ceded the spotlight and moved into other roles, his reputation as a tough, entertaining heel intact.

In an era before every major moment was televised and replayed endlessly, this match still managed to leave a lasting mark.

It redefined both men’s trajectories and anchored one of the better Intercontinental title lineages of the mid‑1980s. It showed how much could be achieved with a clear finish and a receptive crowd, even when the cameras weren’t rolling.

Sources cited are listed below: