Most pro wrestling historians will tell you that Ron Simmons defeated Vader on August 2nd, 1992, to become the first black World Heavyweight Champion.

Dissenters, what few there are, will point to Bobo Brazil’s victory over Buddy Rogers on August 18th, 1962. But it’s Reginald ‘Regis’ Siki who deserves his accolades.

Brazil reigned unrecognized as NWA World Heavyweight Champion for 73 days. But there is one champion the history books leave out, whether by design or by accident.

Nat Fleischer mentions him in passing in his exhaustive 1936 history “From Milo to Londos” and Marcus Griffin fails to mention him at all in his 1937 tell-all “Fall Guys: The Barnums of Bounce.”

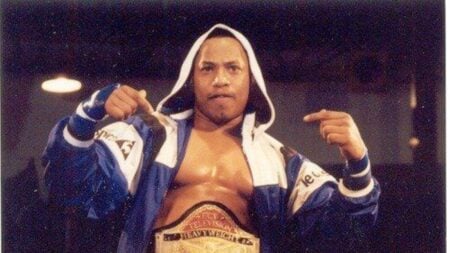

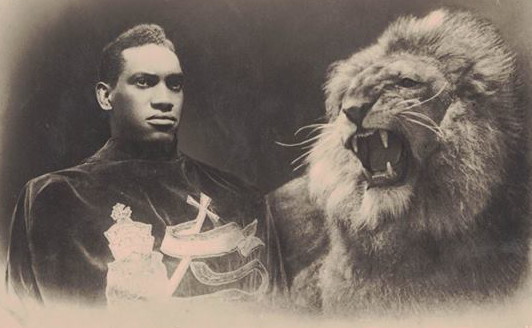

That man is Reginald “Regis” Siki, the first man to hold the World Colored Heavyweight Wrestling Championship.*

While the title itself is an artifact of segregation and a racist relic of a bygone age, it allowed Siki to reach unparalleled levels of success and popularity for his time.

Reginald “Regis” Siki toured the world, competing against the international wrestling greats at the height of segregation and Jim Crow. But who was Reginald “Regis” Siki, and why do we forget him when we think of historic black wrestling champions?

Reginald Siki –

Early Years

Precious little is known of Reginald Siki’s personal life. He left no personal papers and competed in a time before wrestlers gave candid interviews.

What little information we do have is collected from government papers, sports writers, and surviving family. We know that he was born Reginald Berry on December 28th, 1899, in Kansas City, Missouri.

Reginald was one of four children raised by Richard and Ella Berry. Legend has it that Siki was working as a chef at the Zbysko estate in Maine when wrestler and promoter Stanislau Zbysko noticed him.

Zbysko was impressed by Siki’s 6’4″ frame and athletic build, and offered to train him as a wrestler. Siki’s earliest recorded matches come from 1923, against the likes of Wladek Zbysko and Taro Miyake.

It is also at the very beginning of his career that he took on the surname Siki, a reference to Senegalese boxer Battling Siki. The boxing Siki, born Louis Mbarick Fall, defeated Georges Carpentier in 1922 to become World Light Heavyweight Champion.

Legend has it Reginald gained the nickname after some American GIs saw him boxing, however it was more likely the decision of a promoter or even Berry himself.

Becoming Regis Siki came with a few other invented truths. Firstly, Reginald Siki was billed from Abyssinia, or modern-day Ethiopia.

Promoters told reporters bold faced, racist lies, like that his birth name was Dejatch Tedelba or that he was a wild man who hunted and killed animals with his bare hands.

These falsehoods played up the racist caricature of Africa that white audiences believed. However, in promoting Siki as African, he was an exotic attraction for white audiences rather than the grandson of slaves they would have seen him as otherwise.

This also positioned him as one of the ever-growing number of foreign-born wrestlers becoming popular in America at the time. Where African-American wrestlers became regionally popular, Reginald “Regis” Siki was able to make his name as a touring wrestler.

And in the days between Jack Johnson and Joe Louis, Regis Siki became arguably the most popular African-American athlete.

His early in-ring success and popularity, along with connections in the business, lead many sportswriters to speculate that he could become World Heavyweight Wrestling Champion.

World Champion Prospect

While Siki’s star was rising, the original World Heavyweight Wrestling Championship was contested in a program between Joe Stecher and Ed “Strangler” Lewis.

When it came to the new rising star, both men held the same position as boxer Jim Jeffries; that only white athletes were fit to be world champions. While Stecher was more steadfast in his ways, Lewis once stated he would be willing to defend against Siki.

However, Lewis would only take this bout if he received 100% of their cut for the night.

“I don’t take this stand because he is colored,”

Lewis said,

“But due to the fact that the challenger is a giant in size and weight, with what I understand, tremendous strength. I don’t propose to take a chance of losing the title without being well paid for it.”

With Stecher and Lewis refusing Reginald Siki a shot at the championship, promoters began billing him as World Colored Heavyweight Champion beginning in 1924 as a consolation prize.

While this could easily be “Strangler” Lewis covering for his own racism, this could also have been a move to maintain kayfabe.

In the mid 1920’s, when the original World Heavyweight Wrestling Championship was contested by Lewis and Stecher, the majority of pro wrestling bouts in America were pre-determined.

Had Siki ever been in negotiations to face Lewis, he most certainly would have gone in with instructions to lose. Whether Lewis’s offer was genuine it or not, the duo would have been unlikely to find a promoter willing to book the match.

Newspaper reporters at the time often used matches between black and white boxers and wrestlers to stoke racial tensions. For example, sports writers said promoter Lou Daro was “risking a race riot” when he booked Siki against Jim Browning in 1925.

With the World Champions refusing to face him and promoters unwilling to book the match, it seemed as though Siki had gone as far as he could in American wrestling.

After stepping away from the ring for a brief stint as an actor in 1927’s Tarzan and The Golden Lion, Regis Siki departed for Europe in 1928.

International Acclaim

From 1928 to 1930, Regis Siki took part in wrestling tournaments across Eastern Europe. Throughout tournaments in Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Russia, Siki was both the only black competitor and the only American competitor.

He quickly adapted, however, learning to speak multiple languages over his journeys, along with developing a mind for philosophy and an eye for photography.

Also during his voyages, he met and married Ellen Sydenham a Russian-born woman living in Tallinn, Estonia. After getting married in Europe, the couple moved back to America, where they lived in Ohio briefly before moving to Boston.

In Boston, Siki got the biggest push of his career working for Paul Bowser’s AWA, where he challenged Henri DeGlane and Ed Don George for the AWA World Heavyweight Championship.

In late 1933, Reginald and Ellen Siki welcomed their first child, a daughter, into the world. Looking to escape the financial effects of the depression and the discrimination they received in America, the family decided to return to Estonia.

During his original run in Europe, Reginald Siki had developed a reputation as a reliable hand, and soon found himself drawing huge crowds across the continent. He packed the largest football park in Athens for a match against then-World Heavyweight Champion Jim Londos.

A 1935 series against Bulgarian national hero Dan Koloff in Sofia drew an attendance record that stands to this day.

In 1936, he would lose the World Colored Heavyweight Championship to George Godfrey, ending his near 12-year reign as champion, in Brussels, Belgium. Later that year, Reginald and Ellen separated, though did not divorce.

Siki continued wrestling around Europe, eventually settling in Germany in 1937. There, he would live what the Dayton Herald described as “a checkered existence…involving the Gestapo and ‘incidents’ interwoven with wrestling bouts and bombings.”

World War II and Second Wind

When war broke out between England, France, and Germany in 1939, Siki sought a swift exit. He moved to Czechoslovakia, where he converted to Islam and took the name Kemal Abd-Ur Rahman.

Also during this time, he married a woman named Jarmila Fatma, with whom he fathered a son. His last known match in Europe took place in Prague, in June of 1941.

That December, Germany declared war on the United States, and all Americans within the empire were classified as enemies.

By June of 1942, Siki and his family were arrested and imprisoned in Oflag VII-C/Z, a Nazi internment camp located at Tittmoning in Southeastern Bavaria.

In an interview with the Boston Globe, one of the few he ever gave, Siki described how the Nazis treated prisoners at Oflag VII-C/Z.

They were subjected to freezing temperatures and given so little food that Reginald Siki would spend days at a time lying down to make what little caloric intake he had last longer.

“The Nazis kill people like flies…Human life has no value to them.”

For the next two years, Siki, his family, and hundreds of other allied prisoners of war suffered through cold and starvation. In 1944, the Red Cross organized the release of over 300 prisoners from Oflag VII-C/Z, including Siki and his family.

As they made the journey westward, Siki saw the destruction that the war had brought to the countryside.

“It was three days after the Americans had bombed [Augsburg], It was flat…really flat. Fires still smoldered in the ruins. The people stormed the train, trying to get out.”

Upon his return to the United States, Reginald Siki settled in Boston, Massachusetts, where he was re-discovered by his former boss, promoter Paul Bowser.

Within a month of his return from the POW camp, and at 44 years old, Siki resumed his in-ring career, taking bookings along the East coast and into Canada.

In 1946, Siki married his third wife (and first state-recognized wife) Mildred Strader, whereupon the couple moved to California.

Living in Los Angeles, he became a regular competitor at the Olympic Auditorium, working for legendary promoter Jimmy Doyle.

This happened during the ascendance of Gorgeous George, and when Doyle needed a veteran to put George over on national television, Siki took the job.

And so, on December 3rd, 1947, Reginald Siki took a running dropkick to the chin to suffer a loss at the hands of the rising star. However, the loss didn’t break his stride as Reginald Siki continued wrestling at The Olympic every week until June of 1948.

Death and Legacy

The final months of Reginald Siki’s life are murky at best. Rumors persist that he suffered a career-ending injury in his final match at The Olympic against Vic Holbrook.

However, what we do know is that he spent the rest of 1948 traveling the country, looking for new opportunities in the only industry he knew.

Conventional wisdom would suggest Siki had at most another decade of in-ring in him. However, on December 24th, 1948, less than a week away from his 50th birthday, Siki suffered a heart attack.

He was brought to a hospital in Santa Monica, where he was pronounced dead on arrival. On December 31st, he was buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

While little is known about his personal life, what we do know paints a picture of a life that was rich against the odds.

The World Colored Heavyweight Championship may be seen rightly as an albatross around professional wrestling’s neck, but its existence allowed Regis Siki to travel the world, having excellent matches against people of all backgrounds.

As a person, his story of overcoming the odds and surviving the holocaust should be an inspiration to us all.

As a champion, he was an inspiration to a new generation of black wrestlers, including Bearcat Wright, “Sailor” Art Thomas, Reginald “Sweet Daddy” Siki (no relation), and Bobo Brazil, who would defeat Buddy Rogers for the NWA World Heavyweight Championship in 1962.

Despite being given the title to keep the sport segregated, Siki’s accomplishments did more to support integration.