Rivers symbolize freedom. If you place a rock into a river, the water will flow around it. If you block a river, it will cause a flood, or the river will try to forge a new path. Given enough time, a river will wear away any barrier that tries to restrict it. The story of Michinoku Pro-Wrestling is about finding a way around limitations.

It is a universal truth that promoters tend to prefer more prominent athletes with muscular physiques—modern-day giants who can attract fans with their feats of super-strength. Japan is a small island nation. Their potential talent pool is often shallow. Promotions depend on hiring smaller wrestlers and gaijins (non-Japanese) or talent exchanges with neighboring and foreign promotions. The results are often positive for promoters. Yet being the traditionalists that they are, they still prefer their top stars to be superhuman giants.

Mexico has had more influence on Japanese wrestling than any other country. Luchadors may be smaller than average, but they intrigued fans with their colorful costumes and characters. They told stories in the ring using quick acrobatics, high-risk dives, and physical comedy. In the 1980s, New Japan Pro-Wrestling begrudgingly accepted that smaller wrestlers were attracting new audiences.

Michinoku Pro-Wrestling

They began showcasing the Super Juniors, lighter wrestlers from around the world who engaged in faster-paced matches. NJPW took even more tips from lucha libre by creating their own colorful masked characters. Fans loved to see ordinary-sized wrestlers perform superhero-esque feats of athleticism.

Seeing NJPW hire and push smaller performers gave new hope to aspiring wrestlers. They believed they could now make it in an industry that normally shunned them because of their size. One such dreamer was Masanori Murakawa. But he would fail his NJPW entrance exams.

Murakawa found a way around this barrier. Universal Lucha Libre (better known as Universal Pro-Wrestling, or UPW) had just been launched. There were two main reasons why luchadors struggled to make it big in Japan. First, every country had a common wrestling style. Second, Lucha libre had been adapted to be compatible with the U.S. style. It was these adaptions that conflicted with the Japanese format.

Gran Hamada was one of the first Japanese wrestlers to master the lucha libre style. However, being 5’ 6’’, he knew he wouldn’t see the same success in his native country. The aim of UPW was to create a form of lucha libre wrestling that was compatible in Japan and North America. They wanted to cater to an audience that clearly wanted this form of wrestling and to open doors for smaller wrestlers.

Michinoku Pro-Wrestling

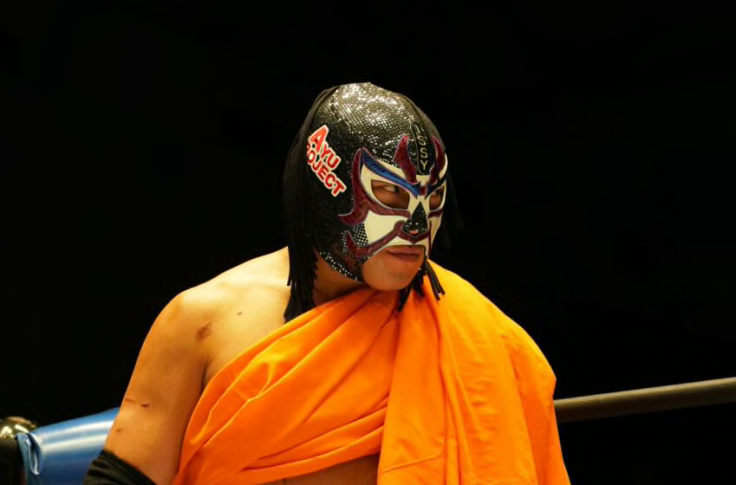

Murakawa was one of the earliest rookies hired by UPW in 1990. It was here that Murakawa was trained in the lucha libre style and had developed his own luchador characters. He got to test his skills and imagination around the world. He finally settled on a black ninja character he called “The Great Sasuke.” Still, relatively early into his career, he suddenly announced he was creating his own promotion.

North Eastern Wrestling was founded in October 1992. It was the first wrestling promotion in Japan to be based outside of the Tokyo region. Collective inexperience and low finances meant it would be six months before they held their first stand-alone shows. It became an unintended offshoot of UPW, with most wrestlers performing in both companies at the same time.

They were introduced to fans as part of a card run by UPW. When they officially launched in March 1993, their card was filled with virtual unknowns. They depended on Hamada being their headline attraction.

Delfin and some of his associates were routinely hired for lightweight shows in other companies, including NJPW’s Super Junior shows.

The company soon changed their name to Michinoku Pro (or M-Pro), reflecting the region they were based in. Then, in late 1994, another popular stable emerged. SATO, Terry Boy, and Shinryu had left UPW to focus on Michinoku Pro-Wrestling. They formed an alliance they named ‘Kai En Tai.’ It was a direct reference to Kaientai, a paramilitary organization that played an instrumental role in ending Imperial rule in Japan.

The original Kaientai served as both a private shipping and trading company and a private navy. It is considered to be Japan’s first corporation. M-Pro’s version also became a runaway success with locals. They were fully repackaged in order to be taken more seriously. SATO was renamed Dick Togo, while Terry Boy became Men’s Teioh.

The stable was rebranded ‘Kaientai Deluxe’ just before they added The Dream Chasers (TAKA Michinoku and Shoichi Funaki). Only Shinryu didn’t undergo a name change. Over the coming years, they added and removed other members such as Hanzo Nakajima, Yoshihiro Tajiri, Super Boy, and even Hamada.

In 1997, M-Pro formed two working relationships with U.S. promotions. The first was with Extreme Championship Wrestling. Members of Michinoku Pro-Wrestling began working matches on ECW cards, mainly in tag team matches pitting babyfaces against “bWo Japan.” This included ECW’s first-ever pay-per-view event, Barely Legal. Sasuke and Hamada teamed with Masato Yakushiji to beat three members of bWo Japan.

Who were bWo Japan? You know them better as Kaientai. World Championship Wrestling had become the top promotion in the U.S., beating out the World Wrestling Federation. Two of their main attractions was the New World Order stable (or nWo) and the Cruiserweights. The latter was a division of lighter wrestlers from around the world who specialized in quick-paced matches, as opposed to the slower contests on WCW T.V.

This was a concept that ECW booker Paul Heyman maintains that WCW stole from them. ECW had a stable informally known as “Raven’s Flock.” The alliance of Stevie Richards, The Blue Meanie, and Nova would do an intentionally poor imitation of wrestlers from other companies or major musical acts before Raven’s matches. After their mimicry of Kiss received an unusually positive reaction, Bubba Ray Dudley recommended they mimic the New World Order.

The bWo (or Blue World Order) went on to become one of the hottest acts in ECW. Someone within ECW noticed parallels between Kaientai and the New World Order. They repackaged Kaientai as “bWo Japan,” a direct mocking of a New World Order sub-faction that competed in NJPW. Teioh reverted back to his old ring name, ‘Terry Boy,’ because it was originally in honor of ECW main-eventer Terry Funk.

This arrangement then led to a second but much shorter relationship with the WWF. Some M-Pro stars began working matches at WWF events. The most notable was when Sasuke beat TAKA at the ‘In Your House 16: Canadian Stampede’ PPV. As part of the exchange, Undertaker went to M-Pro for a brief feud against Jinsei Shinzaki (who had previously competed in WWF as ‘Hakushi’).

It is not known why the relationship with WWF suddenly turned sour. The company realized that they had been slow in capitalizing on the popularity of smaller wrestlers. Many years earlier, the WWF had working relationships with companies in many other countries. As part of their relationship with Universal Wrestling Association (UWA), the WWF introduced the WWF Light Heavyweight Championship at an event in Japan.

The title stayed mainly in the country, unbeknown to most Western fans. It would travel around multiple promotions, including M-Pro, before finally being returned to the WWF in 1997. The company re-introduced it to Western fans as a “new” championship. The first holder of the new title would be the winner of a tournament. Sasuke was the favorite to win before any participants were confirmed.

But it would be TAKA that claimed that honor. Sasuke and M-Pro’s working relationship was finished with the WWF before the tournament ever started. An unfounded rumor alleged that Sasuke had leaked plans for him to win the title to Japanese media and then vowed to never defend it in the U.S. or drop it to a WWF talent. It has since been clarified that this never happened, and the WWF were genuinely more interested in TAKA.

Going Around to Get Over

According to Bruce Pritchard, Heyman encouraged them to work with TAKA instead of Sasuke but did not elaborate on why.

The WWF’s Light Heavyweight Championship wasn’t the only one that found its way into Michinoku Pro-Wrestling. Several lightweight titles were created by other companies in different countries and ultimately became exclusive to Japan. Titles that would be contested in Japan included the UWA World Welterweight Championship, World Junior Light Heavyweight Championship, British Commonwealth Junior Heavyweight Championship, UWF Super Welterweight Championship, and the Independent Junior Heavyweight Championship.

In spite of the drama with the WWF, the relationship with ECW continued on. Michinoku Pro-Wrestling stars continued to work ECW events, again, mainly in tag team matches. A few stars, like Tajiri, would choose to remain in the U.S. Meanwhile, TAKA was pushed as the first face of the WWF’s Light Heavyweight division. His inability to speak English hindered him greatly. He had trouble planning matches with people who didn’t know basic Japanese or Spanish like TAKA did.

Kaientai (Togo, Teioh, and Funaki) were brought in to work with TAKA, with Mr. Yamaguchi-San being brought in as a manager and English-speaking mouthpiece. They recreated Sasuke’s feud with them, but with TAKA in Sasuke’s old role. TAKA would team with various babyfaces to battle them in tag matches. They were essentially an enhancement talent stable, including after TAKA joined them.

Togo and Teioh went back to Japan after a few months. As Funaki was picking up English and the American wrestling style quickly, he stayed on as TAKA’s tag team partner. When TAKA left three years later, Funaki remained in the U.S., mostly working for WWE since.

Sasuke had developed a reputation for his physical toughness. He had repeatedly worked through serious injuries, including a cracked skull, on two occasions. But not even he was superhuman, and he sometimes had to succumb to injury. He was forced to step away from M-Pro while he recovered from knee surgery. He put Delfin in charge after years of proven loyalty.

A few months later, Delfin shocked the company and fans alike by publicly announcing a mass walkout. Delfin launched a rival promotion called Osaka Pro Wrestling. Several M-Pro stars and staff jumped ship with him.

The company attempted a soft reboot at their 10th-anniversary event. This included the introduction of their first exclusive title. The Tohoku Junior Championship was going to be awarded to the winner of a round-robin tournament. In the weeks leading up to the event, wrestlers from around the world (but mainly Japan) competed against each other in singles matches.

Their scores depended on how they earned their victories. The two men with the highest scores then battled for the title at the main show. Dick Togo defeated Tiger Mask IV for the accolade.

In 2003, Sasuke ran for political office. He stepped down and made Shinzaki the interim President while he campaigned. Sasuke won the election and joined the Iwate Prefectural Assembly. He became the first masked legislator in the country’s history. He would give full ownership and control of Michinoku Pro-Wrestling to Shinzaki. The company then became known as “Shinsei Michinoku Pro-Wrestling”.

The death of a partner promotion helped breathe new life into M-Pro. Ultimo Dragon disbanded the Toryumon X promotion. Over the coming months, Dragon and many of his established stars would be added to the Michinoku Pro-Wrestling roster. To signal the new era, Dragon and Shinzaki became the first Tohaku Tag Team Champions.

It wasn’t just Universal Wrestling Association’s singles championships that eventually made their way into Michinoku Pro-Wrestling. Their World Tag Team Championships continued to bounce around various indie promotions after the company closed down in 1995. In 2006, The Brahman Brothers lost the titles to Tohaka Tag Team Champions Ikuto Hidaka and Minoru Fujita. Since then, both championships have been defended together as one.

Their peak came in December 2019. They held a sell-out event at the Korakuen Hall in Tokyo. The show had 1,890 paying fans in attendance, setting a new record for wrestling events at the venue. Unfortunately, they went on hiatus before they could truly capitalize on this momentum due to government lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. They have since resumed, with ‘Bad Boy’ emerging as their main heel stable.

The primary thorn in their side is a trio called Mu no Taisho, who hold all of M-Pro’s active championships at the time of writing.

Every performer who made their way to M-Pro faced restrictions. They were told that their dreams were not possible. Michinoku Pro-Wrestling only exists because people like Hamada and Sasuke tried to find their way around barriers. Everyone who went to M-Pro went they because they were trying to get around barriers. All of the talent that went on to make it in Japan, Mexico, or the U.S. only did so because they got around barriers.

Even the company itself has had to get around barriers and limitations. That is the story of Michinoku Pro-Wrestling.