When Jumbo Tsuruta passed away in May of 2000, my first response was, “Oh yeah… That’s the guy who unified the Triple Crown Championship in All Japan before Stan Hansen beat him for it.”

Shortly thereafter, I was taking a cursory glance at an article that referred to Jumbo Tsuruta as “Japan’s strongest wrestler” and “the greatest Japanese wrestler of all time.”

After all, I had reasoned that any Japanese wrestler worth knowing would have popped up on my home television screen at some point in my life, either during a WWF, NWA, or WCW event. This limited entries into the greatest-ever-from-Japan discussion to wrestlers like Keiji Mutoh, Genichiro Tenryu, Masahiro Chono, and Jushin Liger.

Because I was in the habit of purchasing tapes from Highspots.com on a weekly basis, I figured it was worth spending the $10 to educate myself on the career of this recently deceased wrestler who was allegedly the best.

When the tape arrived, I shed its blue covering, popped it into the VCR, and spent the next 60 minutes absorbing the career retrospective of Jumbo Tsuruta — including the memorial show that followed his death.

The Beginning

Supposedly, Tomomi “Jumbo” Tsuruta was given the gender-neutral name “Tomomi” because his mother believed he was tiny and resembled a girl. However, Tomomi’s growth easily outpaced that of his schoolmates’, and his legitimate 6’5” frame — tall, muscular, and exceedingly rare for a Japanese man in that era — provided Tomomi with advantages in nearly every athletic endeavor he participated in.

Initially, his favorite sport was baseball, but the curse of poor eyesight combined with the advantages of height resulted in Tsuruta turning his focus to basketball.

Regardless of what sport he was involved in, Tsuruta’s endurance was strengthened by his daily bicycle rides home from school, which were entirely uphill, over a stretch of several miles, and along gravel roads.

Apparently, he had no other option but to ride his bike since the bus service in his hometown was unreliable, and the low ceilings of the buses made the voyages exceedingly uncomfortable for a teenager of his height.

Almost as an afterthought, Tsuruta tried his hand in a local sumo wrestling tournament before moving on to Chuo University and finished third in the Yamanishi prefecture’s sumo championship.

Out of frustration caused by the initial reluctance of Japan’s national basketball team to commit to participation in the 1972 Munich Olympics, Tsuruta quit the Chuo University basketball club and took up Greco-Roman wrestling because he felt his natural strength and size, coupled with his hard-won endurance, would effectuate his best opportunity to secure a place for himself on Japan’s Olympic team in any sport.

Shockingly, he was correct. After only a year and a half of training, Tsuruta won two consecutive national championships in Greco-Roman wrestling and earned himself an Olympic berth.

Even without failing to secure any victories during the actual Olympic games, Tsuruta had created a stir due to his quick mastery of Greco-Roman wrestling’s fundamentals and marked himself as a prodigy.

The headlines Tsuruta generated captured the attention of Shohei “Giant” Baba, who by that point was the second most legendary native wrestler in the history of Japan.

Baba’s towering 6’8” frame was aided (and, in certain respects, hindered) by symptoms of acromegaly.

In Baba’s eyes, Tsuruta had the makings of a logical protege; he was a hot commodity due to his amateur wrestling exploits, and his large frame, free of the rigors of acromegaly, would ultimately enable him to be far more athletic, robust and vibrant than Baba ever could have hoped to be.

When Tsuruta publicly announced his intentions to join Baba’s All Japan Pro Wrestling during a press conference held on October 31, 1972, he was immediately dubbed “Wakadaisho” — “The Young Ace.”

Considering how there had truly been only three or four true “aces” in Japanese professional wrestling at that point, including Rikidozan, Giant Baba, Antonio Inoki, and arguably Michiharu Toyonobori, this nickname heaped lofty expectations on the young grappler before he had ever even had his first match.

Tsuruta was quickly shuttled off to the United States to train with the famous Funk wrestling family in Amarillo, Texas.

The patriarch of the family, Dory Funk Sr., was instantly impressed with Tsuruta, claiming that the youngster already had the foundation of wrestling down and simply needed experience in order to improve.

Funk also marveled at Tsuruta’s great strength. Despite possessing the toned, slender physique of an amateur wrestler, and a pair of very long arms, Tsuruta was able to bench press roughly double his body weight with little difficulty.

In October of 1973, just one year after the announcement of his entry into the world of professional wrestling, Tomomi Tsuruta returned to Japan and was quickly thrust into a match for the NWA International Tag Team Championships on the side of Giant Baba against the reigning champions — his mentors, the Funks.

Giant Baba faced criticism for pushing Tsuruta so quickly but invited the fans to come out and judge the young wrestler’s competency for themselves. The Young Ace shocked the fans in attendance at the Kuramae Kokugikan by securing a pinfall on Terry Funk with a gorgeous bridging German suplex.

Although the bout ended in a 1-1 draw, Tsuruta had solidified his place as the number-two native wrestler on the All Japan roster; he would never fall below this position until his retirement from full-time wrestling, two full decades later.

Tsuruta’s spot beneath Baba on the All Japan depth chart came with a new nickname, except this one would be selected by the fans. The results of a contest conducted to promulgate a new ring name for Tsuruta produced “Jumbo” — a product of the burgeoning popularity of jumbo jets in Japan at the time and also of the symmetry of selecting a size-based pseudonym for the successor to a Giant. With that, the era of Jumbo Tsuruta had officially begun.

The United National Champion

Championships in Japan were less about the words that composed the titles’ names and more about the significance and meanings behind the belts the wrestlers wore and carried.

In the Japan Pro Wrestling Association of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the physical NWA International Heavyweight Championship was “The Giant Baba Belt,” just as the NWA United National Championship was “The Antonio Inoki Belt” — or at least it was intended to be until Inoki left the JWA and ultimately founded New Japan Pro Wrestling with himself as the top star.

Then it became “The Seiji Sakaguchi Belt” (a downgrade if ever there was one) until the JWA went out of business.

The United National Championship reemerged in All Japan Pro Wrestling in 1976, from which point it became “The Jumbo Tsuruta Belt” in the truest sense. Between the moment he claimed the UN title in 1976 via a tournament victory over former world champion Jack Brisco and the moment he relinquished the title in 1983 to focus on winning the NWA International Heavyweight Championship, Jumbo Tsuruta held the UN belt for 2,270 out of a possible 2,484 days.

During that era, he contributed to four matches in five years — including a run of three in a row — that were awarded Best Bout by Tokyo Sports magazine. This era clearly marked Jumbo as the next clear megastar of Japan, and there would be no misunderstanding of his coronation when that moment took place.

Jumbo Tsuruta – The Perfect Ace

As the late 1970s gave way to the early 1980s, Tsuruta underwent a series of changes. His Funk-inspired, red-white-and-blue color scheme was replaced by what the Japanese referred to as “ace black.”

Similarly, his colorful ring jacket was replaced by a black jacket with “Jumbo” emblazoned in white script on the left chest, and with the Olympic rings on the back.

Equally as noticeable as Jumbo’s visual changes were his in-ring stylistic changes. His German suplex finishing maneuver was replaced by a combination of Lou-Thesz-inspired maneuvers, including a flying bodyscissors press, and most noticeably a belly-to-back suplex.

Referred to as a “backdrop suplex” in Japan, the maneuver had famously been applied by Thesz to secure a pinfall on Rikidozan himself during one of the pairing’s encounters from 1957, and the papers reported that the precise technique of the hold had been personally taught to Jumbo by Thesz himself.

Emanating from a waist lock position and administered with high velocity, Jumbo’s backdrop suplex was a finishing move befitting a world-class wrestler, especially when he bridged into the maneuver and maintained the waist lock on his opponents to secure his pinfall victories.

In the Puroresu world at the time, there were certain obstacles that were assumed to exist simply because no precedent had been established for the alternative. For instance, Rikidozan reigned as the unchallenged champion of Japan from 1954 to 1963, in a tenure of homeland dominance that was interrupted only by his death.

Following Rikidozan’s murder, his mantle was singularly inherited by Giant Baba. In order to forge his own path to dominance, Antonio Inoki would have to leave the JWA completely in order to escape from Baba’s long shadow.

It would have been quite understandable to assume that Jumbo had already ascended to whatever peak he could realistically be expected to summit because an incumbent Japanese ace champion could only be supplanted in the aftermath of his death.

In an environment where professional wrestlers capable of amassing the requisite financial and political support had typically pushed themselves into the one true main event position in their respective companies and then occupied those positions for decades, Jumbo was the first wrestler who was the honest-to-goodness inheritor of the “ace” title.

After defeating Bruiser Brody for the NWA International Heavyweight Championship, Jumbo Tsuruta was famously told by All Japan’s owner and eternal top star Giant Baba, “You are the ace from now on.”

A full understanding of all of the factors involved is necessary to fully capture the significance of both the statement and the moment. Despite its nominal distinction as being a less-than-world championship, the NWA International Heavyweight Championship was “the Rikidozan championship.”

It was the championship that the grandfather of Puroresu had successfully wrestled away from NWA World Heavyweight Champion Lou Thesz and the title that Rikidozan had held until his death.

When Giant Baba inherited Rikidozan’s top position as the star of Japan Pro Wrestling following his mentor’s murder, a brand new international heavyweight belt was created for Baba to recognize him as the foremost wrestler in Japan and the heir to Rikidozan.

When Baba left JPW in 1972 to found All Japan Pro Wrestling, he left the International belt in JPW, created the Pacific Wrestling Federation as the governing body to sanction All Japan’s championships, and awarded himself the actual, authentic International championship belt worn by Rikidozan as the PWF World Heavyweight Championship.

The tiny, slim belt was soon replaced with a bulkier version more befitting of a wrestler billed as standing close to seven feet tall, but these details convey the layers of symbolism that encircled the NWA International Heavyweight Championship, both in terms of its title and its physical representation and meaning.

After the JPW disbanded in 1973, Kintaro Ohki absconded to Korea with that company’s physical NWA International belt that had been custom-made for Giant Baba and physically worn by him for more than six years, and held onto it until the NWA ordered Ohki to relinquish it back to All Japan in 1981.

For two years, the belt was passed between Dory Funk Jr. and Bruiser Brody before Jumbo finally dethroned Brody.

Baba was the reigning PWF champion at the time, and his proclamation that Jumbo was the ace – over and above Baba – reinforced the idea that the NWA International Heavyweight Champion was still the foremost wrestler in Japan, in the lineage of Rikidozan.

In much the sense that martial arts families pass their stylistic lineages to one another, the royal line of the grandfather of Puroresu had accepted Jumbo as a full grandson.

Also, if we extend this analogy to accept Antonio Inoki of New Japan Pro Wrestling as being Baba’s “brother,” we must still accept that Baba was the first main-event owner of a major Puroresu company to willingly step down and anoint a new superstar in the top position.

This story has often been told with a focus on Baba’s selflessness, but special attention must also be paid to Tsuruta’s worthiness.

The mantle was passed from Rikidozan to Giant Baba only following the former’s passing; this was the first instance of the dominant in-ring position in a Japanese wrestling promotion being willfully transferred from an owner and flagship performer to one of his employees.

From that point forward, Jumbo would hold the international title for the better part of the next six years, with only Stan Hansen and Bruiser Brody being capable of prying it away from him and with neither being capable of doing so for even three months.

The World Champion

One of the problems with the major Japanese professional wrestling companies was their inherent territoriality and their history of subservience to wrestling organizations headquartered in America that were perceived — justifiably or not — to be superior entities.

The irony of the deference paid by Japan’s wrestling companies to U.S.-based organizations is best explained by the fact that Japan’s population in 1975 was 111 million, while the population of the entire United States was 216 million.

If Japan was thought of as a single territory within the NWA, it undeniably serviced the largest population of any singular territory.

While All Japan Pro Wrestling could make a claim to having the highest vintage of non-world-championship titles sanctioned by the National Wrestling Alliance, and also access to the most well-known worldwide wrestling stars.

A certain suspension of disbelief was required in order to accept the fact that Giant Baba could mow down challengers to his Pacific Wrestling Federation throne like grass, and hold that championship for uninterrupted reigns lasting thousands of days, but was somehow incapable of holding the NWA World Heavyweight Championship for more than a week during any of his three reigns.

Facing the problem of not being able to book the NWA champion to appear on any of his shows, Antonio Inoki had attempted to sidestep the roadblock, but with muted results.

First, he invited Karl Gotch, the owner of the apocryphal “Real World Championship” — represented by a physical belt depicting a decades-discontinued championship Gotch had long since lost — to compete in New Japan Pro Wrestling so that he could defeat Gotch to become the Real World Heavyweight Champion.

That coronation failed to establish the traction for Inoki that came with affiliation to a wrestling organization with strong international wrestling ties. The following year, Inoki partnered with (and then outright purchased) the National Wrestling Federation of upstate New York so that he could expand into the United States and headline shows there. The move brutally backfired on Inoki.

The NWF was shut down by the end of 1975, and the one remnant that remained from it was the NWF World Heavyweight Championship belt that adorned Inoki’s waist.

Inoki quickly applied for admission to the National Wrestling Alliance, and just like what happened with Baba’s PWF championship, Inoki acquiesced to the wishes of the NWA and stopped openly referring to the NWF title as a “world championship.”

However, Inoki never got around to updating the appearance of the belt to remove the word “world” from its main plate. Inoki would later seize the World Wide Wrestling Federation championship under dubious circumstances, beginning a very short title reign that was never acknowledged in the United States.

However, in Japan, the short reign could be said to mark Inoki’s third reign with a third different world championship, even if the championships were of questionable quality, and even if the reigns were accumulated under suspicious circumstances.

In other words, the NWA International Heavyweight Championship may have been the “treasure of the Japanese mat world,” but it was always cast as inferior to world titles that were managed by offices located overseas.

In order to be fairly compared with Baba and Inoki, who had both had reigns as world champions of debatable credibility, a world championship needed to land on Jumbo’s doorstep at some point during the prime of his career.

Unfortunately for Jumbo, his ascension to the outright ace position in All Japan coincided with the incommensurate shift in the balance of power within the National Wrestling Alliance territories to the American-based fiefdoms located in Dallas, Atlanta and Charlotte, making it less likely that a world title reign — even a short one — would ever be allocated to Tsuruta.

Locally, Jumbo had been forced to carry the title of “Good fighting man,” meaning that Jumbo was good, but not truly great at the level that the true world champions had been.

Fortunately, there was another respectable world championship that could be placed up for grabs.

The world title of the American Wrestling Association — an organization with a territory comprising several within the Upper Midwestern United States, along with the major cities of several outlying states capable of contributing respectably-sized audiences — had been defended in Japan for several years by the likes of Verne Gagne and Nick Bockwinkel.

In his role as the AWA’s owner, Verne had proven to be willing to accept money in exchange for permitting people he respected to briefly hold his company’s flagship championship, having done so in 1982 by granting a two-week reign to Otto Wanz of Austria.

In early 1984, Gagne and Baba reached an agreement that would convincingly vault Tsuruta into the upper echelon of “Tsurufuji” — a name concocted by the Japanese wrestling media to collectively refer to the next generation aces of All Japan and New Japan respectively: Jumbo Tsuruta and Tatsumi Fujinami.

On February 22, 1984, Jumbo Tsuruta delivered his bridging backdrop-hold finishing maneuver to Nick Bockwinkel while Terry Funk counted the pinfall in his role as special referee.

The win marked Tsuruta as the first wrestler in his generation to capture a respectable world championship controlled by a major American promotion.

While Inoki would spend a further three years winning every major championship his organization could control, Jumbo received a significant head start over his peers by virtue of his AWA title victory.

What’s more, Jumbo retained the championship in his rematch with Bockwinkel, clueing fans in to the fact that Jumbo’s title reign would not be as short as Baba’s NWA title reigns had been. In fact, Jumbo went on to successfully defend the AWA championship — in the United States no less — a further 15 times before dropping the belt to Rick Martel after 81 days.

Riki Choshu and Japan Pro Wrestling

A real-life financial dispute in New Japan Pro Wrestling led to a structural fissure in the organization, and ultimately resulted in the exodus of several of the most entertaining and promising wrestlers from the New Japan Pro Wrestling roster under the banner of Japan Pro Wrestling.

Two of the participants in that exodus would ultimately have major repercussions on the progression of Jumbo Tsuruta’s career.

The entity known as “New Japan Pro Wrestling Kogyu/Industries” would soon rebrand itself as “Japan Pro Wrestling,” and it would reach a contractual agreement to co-promote with All Japan Pro Wrestling.

For all intents and purposes, what transpired was an invasion of All Japan by Japan Pro Wrestling, and wrestling fans were anxious to see a series of dream matches pitting Jumbo Tsuruta and Genichiro Tenryu against Riki Choshu — arguably the most popular wrestler in all of Japan, who had been a legitimate dark-horse candidate to inherit Antonio Inoki’s role as the ace of New Japan Pro Wrestling.

When the dream clash between Tsuruta and Choshu did occur, it marked a crucial point in the progression of the wrestling style of All Japan.

The traditional, by-the-numbers approach to wrestling in AJPW had been criticized by many fans as being predictable, slow-paced, and stale in comparison to the fast-paced, frenzied action often typified by wrestlers like Inoki, Tiger Mask, Tatsumi Fujinami, and Choshu.

Choshu was openly critical of Jumbo before their initial bout, dismissing Tsuruta and his style by saying the All-Japan ace wrestled and presented himself as if he had been “soaked in lukewarm water.”

The actual contest between the two would eventually be regarded as legendary. The bout began as a run-of-the-mill All Japan Pro Wrestling contest and built in its freneticism over the course of a full hour so that the pace of the action was elevated as the bout grew longer.

Jumbo proved he was able to match the pace of Choshu’s vaunted “high-spurt” offense and matched the famous Riki Lariat with the memorable unveiling of the Jumbo Lariat.

When it was over with, Choshu praised Jumbo, saying that if the contest had been judged like a boxing match, Choshu would certainly have lost.

After more than a year in AJPW, Choshu left the company under conditions that Giant Baba declared to have been less-than-honorable.

In his wake, Choshu left behind his tag team partner Yoshiaki Yatsu — a multi-time Olympic wrestler who had once been heralded as the future of New Japan Pro Wrestling before Choshu had absconded to All Japan with him.

Tsuruta snatched up Yatsu as his tag team partner, forming a tag team of former Olympians known as “The Olympics.”

The pairing was highly successful, winning the PWF World Tag Team Championship and then unifying that title with the NWA International Tag Team Championship just six days later to create AJPW’s unified World Tag Team Championship.

The team continued its success by losing and regaining the championship four additional times over the course of the next year before the behind-the-scenes machinations of Genichiro Tenryu would render future teamings of The Olympics to be an impossibility.

Jumbo Tsuruta –

The Triple Crown, and the War with Hansen and Tenryu

After Jumbo decided to surrender the United National Championship and divert his efforts to capturing the NWA International Heavyweight Championship, the UN belt had been passed over to Genichiro Tenryu after Ted Dibiase kept the belt warm for a few months.

With the transfer of the UN belt came the elevation of Tenryu to the unquestioned position of number-two native wrestler in All Japan Pro Wrestling.

By 1988, the Japanese wrestling media had officially expanded “Tsurufuji” to include both Tenryu and Riki Choshu, redubbing this class of multi-company stars as “Tsurufujichoten.”

Tenryu had earned his position within the foursome by becoming the first wrestler other than Antonio Inoki to win the Tokyo Sports award for MVP of wrestling three times and tied Inoki’s longest streak by doing so for three years in a row.

In the backdrop of this, Stan Hansen had defeated Baba for the PWF Heavyweight Championship and then marked himself as the only gaijin wrestler capable of stringing together multiple lengthy, 200-plus day reigns with the championship that had come to symbolize Baba during the strong second act of the legend’s career.

Hansen had also enjoyed a reign as AWA World Heavyweight Champion, defended the championship in All Japan, and never surrendered the belt in the ring.

It was in the midst of this environment, with the three standout stars on his roster clearly identified (four including Bruiser Brody, who would be tragically murdered in a Puerto Rican locker room in 1988) that Baba made the decision to withdraw from the National Wrestling Alliance.

The financial troubles of Jim Crockett Promotions and their territorial stranglehold over the NWA World Heavyweight Championship were part of their problem, as was the acquisition of JCP by Ted Turner, and the creation of World Championship Wrestling.

Baba quickly made the first move toward a title unification, having Tenryu and Hansen trade victories to merge the UN and PWF titles into a single championship.

According to Dave Meltzer of the wrestling observer, the booking of Genichiro Tenryu during his six-man tag team match at Clash of the Champions V created a preposterous scenario that couldn’t be explained to Baba’s audience of fans who were used to a comparatively pure, sports-based presentation with minimal silliness.

With this event acting as the final straw, Baba formally withdrew All Japan Pro Wrestling from the National Wrestling Alliance, and pulled the trigger on the creation of his own world championship.

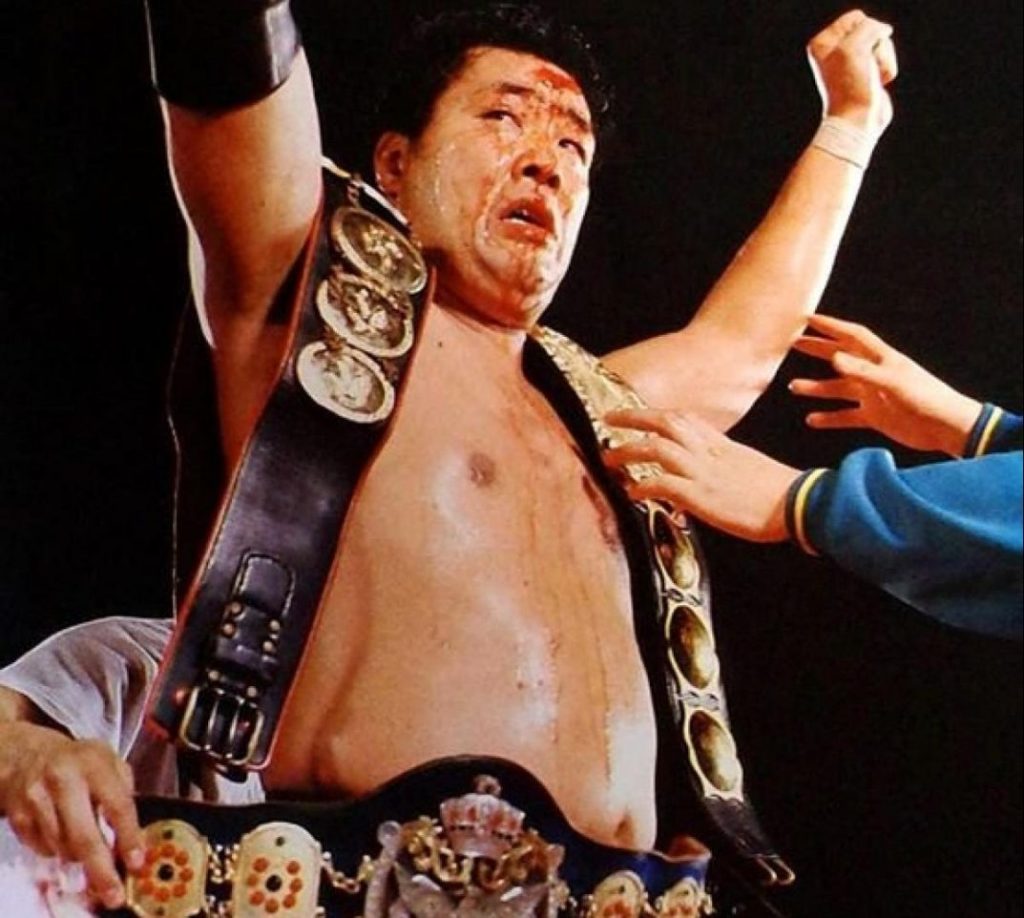

On April 18, 1989, Jumbo Tsuruta defeated Stan Hansen to unify all of the singles championship of All Japan Pro Wrestling into a single entity.

As far as sanctioning was concerned, the International and UN titles no longer held any official ties to the National Wrestling Alliance. However, this was an instance in which only the eyeball test mattered; the Baba-Hansen Belt, Rikidozan-Baba Belt, and Inoki-Jumbo-Tenryu Belt had all been unified into one championship.

With that, the Triple Crown Championship became the ultimate collection of baubles tied to Puroresu’s rich history, and it was soon accompanied by the Nippon TV trophy, which had the words “World Heavyweight Champion” etched into its side.

Shortly following his coronation as All Japan’s first in-house world champion, Jumbo Tsuruta engaged in a series of matches with Genichiro Tenryu that indelibly established the expectations for what a main-event, world championship match should be in Japan in a way that carries forward to this very day.

In fact, the aftereffects of the series are still being on both sides of the Pacific, in ways that are both positive and negative.

A couple years prior, Shinichi Takano recounted an incident that supposedly awakened a version of Jumbo Tsuruta that would eventually come to be known as “Kaibutsu” — The Monster.

During a tag team match pitting Tsuruta and Tenryu against Takano and Yatsu, Takano inadvertently caught Tsuruta with a stiff missile dropkick to the face, thereby causing the ace to bleed.

Enraged, Jumbo unloaded on Takano with a lariat that was stiffer than usual, a jumping knee strike that was far more direct in its delivery to Takano’s face, and a backdrop suplex delivered at an angle that brought Takano’s head crashing to the mat.

According to Takano, Giant Baba was grateful at what the stiff dropkick had unlocked in Jumbo. Despite Jumbo’s great size and strength, he had grown to be regarded as a wrestler who was somehow too polite, and who wrestled beneath the full violent physical potential that someone of his might was thought to be capable of.

Just in time to change the face of wrestling forever, Takano had awakened the untapped potential of a monster.

While Ric Flair and Ricky Steamboat were offering American wrestling fans an idealized view of what a traditional NWA-territorial match should look like, when executed by arguably the very best who had ever portrayed the traditional face-heel dynamic in a wrestling ring, Tsuruta and Tenryu were laying the foundation for the future of wrestling, when two popular babyface wrestlers would collide, and the outcome was required to be conclusive.

In comparison to the Flair-Steamboat series, Tsuruta and Tenryu went to war.

Every strike between the two made clear and obvious contact. As Tsuruta had now permanently transitioned into the post-Takano-dropkick version of himself, his signature jumping knee strikes, which had previously been delivered in an angled, just-off-the-mark fashion, became jarringly precise in their rate of direct connections with Tenryu’s chin.

Their bone-jarring lariats echoed through the arena and visibly knocked the sweat from one another’s bodies. The two countered and re-countered one another’s moves in ways that communicated logical familiarity with one another that was hitherto unseen inside of a wrestling ring.

The way in which moves were exhaustingly sidestepped or limbs were clutched out of desperation to avoid being smashed against the mat conveyed the sheer fear of defeat better than possibly any other match to date.

Finishing moves that were delivered with unprecedented and staggering impact — like high-angle backdrop suplexes and powerbombs — were kicked out of repeatedly, establishing the principle that it takes more than one use of your most devastating maneuver to dethrone a proper ace.

When Tenryu pinned Jumbo to capture the Triple Crown Heavyweight Championship on June 5, 1989, he had done so following what was arguably the greatest heavyweight match in the history of wrestling up until that point.

He became the first native Japanese wrestler to pin Jumbo cleanly since Giant Baba had done so many years prior. Also, by rejecting Jumbo’s post-match attempt at a handshake, Tenryu demonstrated that he didn’t need the acknowledgment of the ace to make his coronation complete.

The war between Tenryu and Tsuruta fully fleshed out what the King’s/Royal Road Wrestling Style would become. First coined by wrestling critic Takashi Kikuchi — and based on the idea that the style was birthed by Rikidozan in the Riki Sports Palace, which was the first true venue constructed to showcase professional wrestling in Japan — the royal wrestling style was said by Giant Baba to emphasize the importance of receiving and withstanding the best efforts of the opponent by developing a body capable of absorbing an adversary’s strongest attacks while still emerging victorious.

While this style of wrestling would be raised to a dangerous level of head-dropping absurdity in subsequent years, its development through the efforts of Tsuruta and Tenryu was memorable and a pleasure to witness.

The Kaibutsu Era

While Tsuruta and Tenryu were redefining what professional wrestling would look like in subsequent decades, events were underway that would drastically alter the landscape of professional wrestling in Japan.

Eyeglass megacorporation Megane Super formed the Super World of Sports wrestling company and began offering sizable contracts to established Japanese wrestling stars, and then they formalized a partnership with the World Wrestling Federation.

Although SWS was ultimately a long-term failure, and was out of business within three years, it forced Giant Baba to dramatically shift the roles of the players within his talent roster, and also to modify his long-time booking practices.

In particular, the defections of Tenryu left a gaping hole at the top of the All Japan wrestling cards. Moreover, it exposed how woefully flatfooted Baba would be caught if an injury or some other unfortunate occurrence befell Jumbo, his only remaining native wrestler with any true main-event credibility.

The defections also exposed another problem: Not only had Tenryu been established as the only native athlete on All Japan’s roster who could compete with Jumbo move for move, but he was also one year older than Jumbo.

To quickly counter the two-tiered problem posed by the main-event vacancy and the absence of a future star who had been clearly anointed, Baba arranged for the dramatic unmasking and elevation of Mitsuharu Misawa — the second Tiger Mask.

During a tag team contest against Hiromichi Fuyuki and Yoshiaki Yatsu (ironically, two wrestlers who would also soon defect to SWS alongside Tenryu), Misawa would request that his partner Toshiaki Kawada remove his mask for him. Misawa would then dominate the remainder of the match.

Subsequently, Misawa and Jumbo engaged in a heated exchange during a tag team match in which they were on opposing sides, leading directly to the first one-on-one counter between the two following Misawa’s unmasking. Jumbo had dominated all prior encounters with Misawa, but Misawa made it clear that he would show All Japan’s reigning ace no respect.

In a move echoing Tenryu’s tactical display of disrespect, Misawa refused Jumbo’s pre-match handshake, slapped him around, and then repeatedly outmaneuvered Jumbo at the end of the match to gain a pinfall victory over Jumbo that was shocking and satisfying, albeit far from convincing.

Even so, Misawa had managed to become the only native All Japan wrestling star other than Baba and Tenryu to pin Jumbo’s shoulders to the mat over the course of his 17-year career, and the accomplishment was sufficient to thrust Misawa into the role of being “The Standard Bearer for Future Generations.”

With a new native-versus-native rivalry beginning to simmer, Baba booked the feud between Tsuruta-gun and the Over Generation Army, in which Tsuruta and his allies — Masanobu Fuchi and Akira Taue — fought to keep Misawa and his crew — Toshiaki Kawada, Kenta Kobashi and Tsuyoshi Kokuchi — in their place.

Jumbo’s demeanor notably changed during this feud. Over the course of a one-year reign as Triple Crown Heavyweight Champion, Jumbo Tsuruta fully established his nickname of “Kaibutsu no sho.”

Jumbo’s execution of moves became noticeably more vicious. The angle of his backdrop suplexes drifted even more from obtuse to rightward, and he bullied his young opponents by repeatedly suplexing them onto their necks before bringing the curtain crashing down upon them with his backdrop-hold maneuver.

All of this was punctuated by Jumbo’s incessant appeals to the crowd, and his constant vocalization of “Oh!”. Jumbo Tsuruta made it crystal clear that he would not only be slapping around and torturing the young punks, but he was enjoying it, and he wanted you to know that he was enjoying it.

During this era, Tsuruta convincingly turned back the challenge of young Misawa and pinned him twice following sequences of devastating backdrop suplexes, making it patently obvious that the emerald-clad grappler’s presumed ascension to the All Japan throne would come at a heavy price.

Jumbo Tsuruta – The Ultimate Anticlimax

The final two in-ring clashes between Tsuruta and Misawa were eventful affairs. Taking advantage of a well-timed clothesline to the back of Jumbo’s head — courtesy of Toshiaki Kawada — just as Jumbo was preparing to close the show yet again with his devastating sequence of suplexes, Misawa secured an unfathomable victory over Tsuruta through the use of a German suplex, followed by a facelock submission hold.

However, despite the victory, Misawa had not yet proven that he could absorb Tsuruta’s best in a one-on-one encounter before rendering the Perfect Ace comatose on the mat, as Tenryu had.

Misawa would battle “Kaibutsu no sho” to a draw during their ensuing Champion Carnival matchup, proving that he could at least rise to the occasion and battle the enraged edition of Jumbo to a standstill. Unfortunately, that would be the best chance Misawa would ever have.

With a logical ascension plan in place, where Misawa would prove his mettle against Tsuruta and earn the role of “ace” in a climactic battle, it would be an invisible foe that would eliminate the most imposing obstacle from Misawa’s path and render his crowning as an anticlimactic affair.

It wasn’t one of Misawa’s scorching elbows that would unseat Jumbo from his perch. Instead, it was a diagnosis of Hepatitis B.

When Jumbo Tsuruta eventually returned to part-time in-ring action, he was relegated to comedic, six-man tag matches with the old-timers. His strong, if not distinctively muscular physique soon shriveled up from prolonged exposure to the debilitating disease and rendered Tsuruta as a shell of his former self.

It was a sad, precipitous downturn to a 20-year wrestling career that had started at the top and then grown from there.

It’s worth pointing out that Jumbo’s ascension to the supreme tier of professional wrestling would not have occurred so smoothly without the selflessness of Baba, who had the wherewithal to demote himself willingly to make way for the future.

Conversely, Antonio Inoki would cling to relevancy for dear life, resulting in credibility-destroying moments — like booking himself to bodyslam Andre the Giant when the eyeball test rendered such a feat as a clear impossibility — and also slowing the natural progression of his company.

The most logical heir to Inoki’s kingdom was Tatsumi Fujinami, and everyone knew it. Fujinami and Tsuruta were marked as the successors to the handpicked heirs of Rikidozan for many years.

Yet, Inoki delayed Fujinami’s ascension by a further five years, giving Tsuruta a massive head start as a flagship performer. By comparison, Fujinami peaked just long enough to suffer a major injury and then to hand New Japan over to Keiji Mutoh, Masahiro Chono, and Shinya Hashimoto.

There would be no decade of unmistakable dominance for “The Dragon” as there had been for “The Monster.”

Staring up at the lights

Jumbo Tsuruta eventually departed with his family for the United States, as he acquired a role as a visiting researcher at Portland State University. However, his tenure in the U.S. would be brief. His Hepatitis B was soon exacerbated into full-blown liver cancer.

Jumbo was given a round of anesthetic and stared at the ceiling lights until unconsciousness befell him. It was only on the rarest of occasions that Tsuruta was ever left prostrate on the canvas, staring up at the lights.

It would be a sad irony that the ceiling lights of the National Kidney Research Institute of the Philippines were likely the last sight Tsuruta would ever see in this world. The Perfect Ace never regained consciousness. He died during surgery at 4:00 p.m. on May 13, 2000.

At the Jumbo Tsuruta Memorial Show, the generation raised by Jumbo Tsuruta paid their final respects. Misawa carried a flower-rimmed portrait of Tsuruta into the ring and held it during a 10-bell salute.

The portrait then remained in a position of honor in the front row as the wrestlers on All Japan’s roster competed against one another, and then paid their respects to a wrestler who — all things considered — may have been the greatest of all time.

The newest young All Japan wrestler earmarked for superstardom — Jun Akiyama — paid the most obvious in-ring tribute to Jumbo by unleashing a beautiful jumping knee attack on Jackie Fulton (George Hines), and then turning to the portrait of Jumbo in clear deference to the wrestler who had spent more than a decade executing the maneuver as a staple of his in-ring arsenal.

Of course, the passing of the Perfect Ace was preceded by the death of his mentor and predecessor, Giant Baba. The man who had been both a legendary wrestler and booker succumbed to liver failure resulting from colon cancer the prior year, in January of 1999.

It was sadly fitting that the two would follow one another into the hereafter in quick succession, as the architects who had first laid the foundation for the King’s Road style in All Japan wouldn’t be present to witness its demolition.

Misawa would begin the process of absconding with the bulk of the AJPW roster to form Pro Wrestling Noah in late May through his resignation from the AJPW Board of Directors, just one month after Jumbo’s death.

Jumbo Tsuruta – The Legacy of the Monster

Between 1976 and 1992, Jumbo Tsuruta was an annual contender for the title of the world’s best wrestler, and his streak was only cut short by a debilitating illness.

After 1977, Tatsumi Fujinami and others in New Japan were clearly better than Antonio Inoki bell-to-bell, but Fujinami was certainly no longer in New Japan’s best-worker discussion by 1990 when Jushin Liger was presiding over the junior heavyweight division.

By comparison, Misawa, Kawada, and other All Japan performers may have been flashier workers than Jumbo by 1992, but whether or not they were legitimately better in the ring remains an unsettled debate.

However, of arguably greater significance than Jumbo’s lengthy chain of excellent performances is his indelible and enduring contribution to wrestling’s progression while he was at the peak of his powers.

His matches against Tenryu were genre-changing. Not only do they hold up to scrutiny more than 30 years later, but they established the framework for what heavyweight professional wrestling should aspire to be at its apex.

A description of a sequence from the final throwaway match between the two titans in 1990 sounds like an exchange between two wrestlers at a New Japan event in 2020:

Tsuruta attempts a Thesz press, but Tenryu hotshots him into the ropes. Tenryu secures Jumbo’s legs and flips over into a pin attempt, but Jumbo floats over for a nearfall.

He sidesteps a Jumbo lariat, hooks on a full nelson, and bridges backwards with it into another nearfall. Tenryu then clobbers Tsuruta with an enzuigiri and goes for a powerbomb, but Jumbo grabs Tenryu’s legs, then his arms, falls backwards, and reverses it into a pin attempt.

He rolls over, maintains his grasp of Jumbo’s waist, and lifts Tsuruta off the mat for a second powerbomb attempt, only for Tsuruta to whip his legs up and boot Tenryu in the head.

Tenryu attempts a lariat, but is met with a brutal boot to the face, followed by two forearms in the corner, an Irish whip to the opposing corner, a savage corner lariat, and Jumbo’s famous “Oh!” appeal to the fans, with his fist raised in a boisterous salute. Tsuruta then hits his backdrop suplex, but Tenryu manages to kick out of the pinfall.

Jumbo tries a neckbreaker, which the dazed Tenryu reverses into a panicked backslide for a two count. Capitalizing on Tenryu’s disorientation, Jumbo quickly forearms him, and finishes him with a bridging backdrop suplex for three.

That sequence still holds up 30 years later, and it still holds up because this guy was the best.