Not many professional wrestling promotions can claim to have revolutionized the landscape of professional wrestling in their country.

Some, like WWE, became global phenomena, while others, like New Japan Pro Wrestling, cultivated icons of a hard-hitting style that spread overseas.

Yet not all promotions reach these heights, and the best of those that don’t carve out their own niche in professional wrestling, which is where we find Big Japan Pro Wrestling (BJW).

BJW navigated the turbulent world of Japanese professional wrestling in the 1990s during the boom of a bloody and violent style known as deathmatch wrestling.

Navigating such a diverse landscape was not easy task however, and here we look at how the dreams of Big Japan Pro Wrestling’s founders guided the promotion to a successful start that laid the foundations for years to come.

BJW – Deathmatch Wrestling

Much like other forms of entertainment, professional wrestling has multiple genres that resonate with both performers and fans globally.

Within Japan’s Kanto region alone, a rich array of wrestling styles have flourished over the years.

From the work-rate-focused promotions challenging titans like New Japan Pro Wrestling and All Japan Pro Wrestling to those embracing the spectacle of Mexican lucha libre or the larger-than-life phenomenon of Western entertainment.

Even avant-garde comedy can find its stage within pro-wrestling’s vibrant landscape.

Amidst this diversity, a niche for visceral and increasingly violent displays emerges. Each fan may have their threshold for intensity, but across promotions, the spectrum of violence is vast.

Some merely sprinkle their events with weaponized theatrics, while others make them the cornerstone of their identity.

This diversity brings into question how we classify matches featuring weapons in pro-wrestling. The line blurs between standard fare and the more extreme, where a routine bout can swiftly devolve into a chaotic melee of steel chairs and splintered tables.

It’s the promotions that consistently offer the latter, heightened level of aggression that truly earn the label of hardcore.

But if hardcore promotions represent a significant escalation in violence from the mainstream, there are those that seek to push the boundaries even further. These are the realms of deathmatch wrestling.

While hardcore matches tend to feature tables, ladders, chairs, and a limited usage of more dangerous weapons, deathmatches boast a far more menacing arsenal, encompassing anything and everything as potential weapons.

Glass and barbed wire stand as staples, their forms and applications shaping the brutal story of each match, but don’t be surprised to see other devastating inclusions.

Yet in this carnage, there’s a surprising versatility to deathmatch wrestling. With few rules constraining its narrative, it seamlessly blends elements of comedy, technical prowess, and sheer brutality.

In the midst of shattered glass and spilled blood, there lies a canvas where the unexpected thrives, and the boundaries of wrestling are pushed to their limit.

The Lay Of The Land

On March 16th, 1995, the world of professional wrestling was introduced to Big Japan Pro Wrestling (BJW), a new promotion that no doubt aspired to become a force in Japanese professional wrestling and the premier hardcore/deathmatch promotion worldwide.

However, it’s worth noting that the mid-1990s was a period in which hardcore and deathmatch wrestling was considered to be at its apex, meaning that there was plenty of pre-existing competition that Big Japan Pro Wrestling had to contend with after starting up.

At the top of the mountain sat Frontier Martial-Arts Wrestling (FMW), a six year old promotion founded by deathmatch icon Atsushi Onita.

When people look back and talk about deathmatch wrestling in the 90s, especially Japanese deathmatch wrestling, they’re more often than not talking about Onita’s FMW and for good reason.

In its early years, FMW had an eclectic mix of styles, be it showcasing the best martial artists from Japan and the United States or the bloody deathmatches they’re remembered for today.

They would even have female wrestlers work on their shows, something that could only usually be seen in Japan when watching a Joshi wrestling promotion like All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling. Even then, you wouldn’t see these women dropping as much blood as they did in FMW.

As the years passed, Onita took note of what the fans seemed to enjoy most and that was the promotion’s deathmatches while the martial-arts portions of FMW’s shows were slowly phased out.

It was the stars, quality and the absurdity that featured on each show that earned FMW their place at the top of the deathmatch mountain in this period.

Onita himself was a massive draw due to his willingness to put his body through Hell for the fans’ entertainment; the passion he showed in his matches helped to elevate those around him, particularly in his feud with Tarzan Goto.

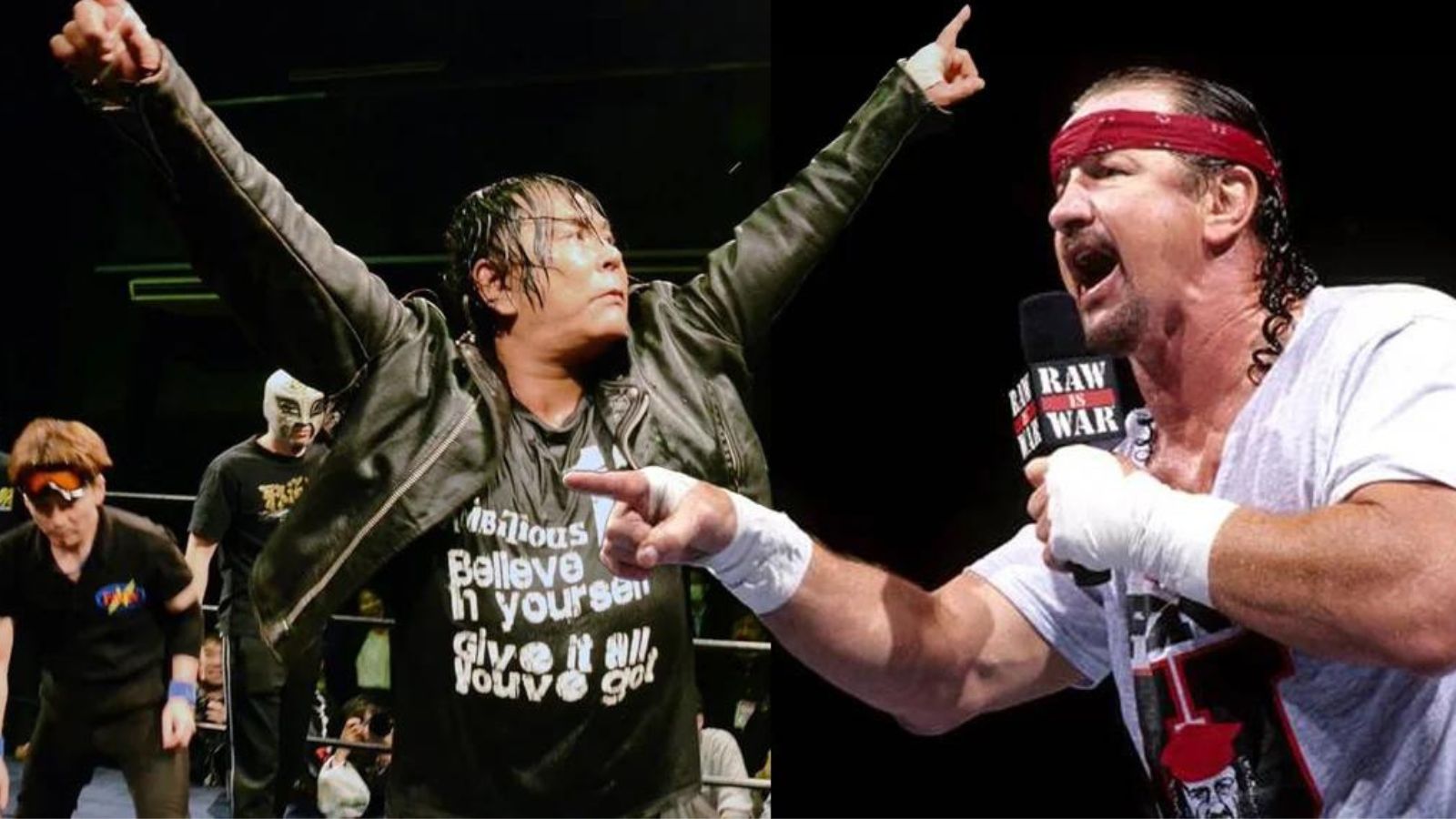

The addition of stars from the United States would also add to the appeal of FMW, with the likes of The Sheik, Sabu and Chris Jericho all making appearances.

Onita vs. Funk embodied everything that the promotion was about at the time; it had all the components of a deathmatch combined with a level of storytelling and passion usually reserved for Oscar nominations.

As if all of this wasn’t already difficult to match up to, FMW would draw crowds of over 2,000 consistently, a number which only increased as Onita’s six-month retirement tour took place from January 1995 onwards.

The incoming retirement of Atsushi Onita wouldn’t help matters for other promotions hoping to make their mark on the style, as FMW had an Ace in the hole by the name of Eiji Ezaki, better known as Hayabusa, ready to take his place at the top.

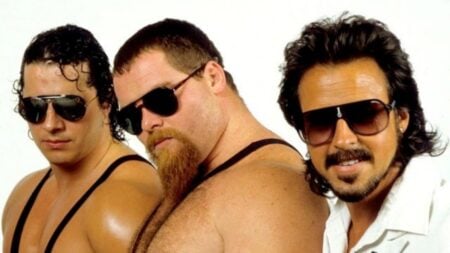

FMW were not the only promotion that BJW had to contend with in 1995. International Wrestling Association Japan (IWA Japan) was another promotion that had adopted deathmatches as a fixture at their events and sat just below FMW in the pecking order.

They had formed just a year prior to BJW in order to fill a gap created by the closure of Wrestling International New Generations (W*ING), and their founder, Victor Quiñones, had plenty of experience in deathmatch promotions, having been involved in both FMW and W*ING prior to starting IWA Japan.

The promotion would use primarily ex-W*ING talent, effectively absorbing W*ING’s fanbase in the process.

Though IWA Japan would also add to their roster a number of foreign stars including Terry Funk and Tiger Jeet Singh. In terms of attendance, IWA Japan would bring in anywhere between 1,000-2,000 consistently with their larger events breaking the 3,000 mark.

1995 would turn out to be a crucial year for the deathmatch scene and changes would come in waves as the months went by.

Come March, the scene was set for Big Japan Pro Wrestling to make their debut in the world of professional wrestling and make their mark in the already chaotic realm of deathmatch wrestling.

The Founders

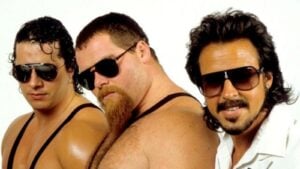

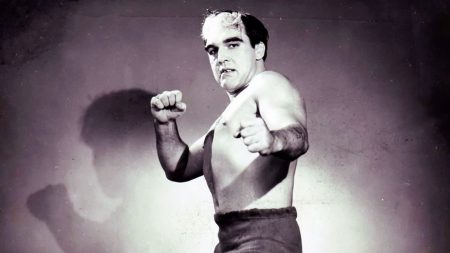

Big Japan Pro Wrestling was the brainchild of Shinya Kojika and Kendo Nagasaki, both of whom were professional wrestlers who excelled at the hardcore style of wrestling and had a combined fifty-six years of in-ring experience when BJW was formed.

Their partnership dates back to sometime before 1995 when the two worked together in All Japan Pro Wrestling though.

To understand what made these two stalwarts of the industry a perfect fit for Big Japan Pro Wrestling, it’s worth looking at which roads they took in their careers that led to them forming BJW.

Shinya Kojika and Kazuo Sakurada traversed different paths through the world of professional wrestling. However, their experiences underscored a crucial distinction: what resonated in the West found little resonance in Japan.

While Western audiences revelled in Kojika and Sakurada’s merciless dismantling of opponents with improvised weaponry, such spectacles failed to captivate fans in Japan’s two most prestigious promotions, All Japan and New Japan.

However, this isn’t to suggest that Japan lacked an appetite for hardcore wrestling, as evidenced by the emergence of FMW and IWA Japan, among others.

Yet, garnering favour with the audience in such promotions proved challenging; few could match the emotional depth and narrative prowess of Atsushi Onita, whose bond with fans was unparalleled, not to mention his willingness to endure physical torment for their admiration.

Sakurada found himself adrift after severing ties with FMW in favour of Super World of Sports (SWS), leaving him bereft of a platform to showcase his hardcore and martial arts expertise as a top-tier star.

Thus, he birthed Network of Wrestling (NOW). Unfortunately, Sakurada’s endeavour coincided with the impending surge of deathmatch and hardcore wrestling, diverging from NOW’s focus on strong style and martial arts showcases.

Luckily for him, there was another individual who had struggled to find a platform in Japan almost a decade earlier and had since moved into a backstage role within the industry.

Shinya Kojika joined forces with Sakurada, who he had known throughout Sakurada’s time with All Japan, and he brought with him a wealth of industry knowledge along with an eagerness to show Japan his vision for professional wrestling.

Sakurada would also bring with him the young Eiji Tosaka, whom he had worked with in both SWS and NOW.

Tosaka was and still is a multi-talented man, capable of performing roles at the commentary desk, as a referee and as a promoter, making him an invaluable asset to the promotion and one that BJW would hope to keep around for the long run.

With that, Big Japan Pro Wrestling was born, where the deathmatch style would be placed at the core of the promotion while still allowing for matches of other styles to build up anticipation for a bloody main event.

Now all that remained to be seen was just how far this team could take Japan’s newest alternative to the mainstream.