When the professional wrestling contributions of Woodrow “Woody” Wilson Strode are introduced into conversations by well-meaning mat historians, the establishment of his significance is often handled in an inductive formula of A + B + C + D = E.

In this case, since Strode was A – at least half Black – and B – a successful football player – who C – became a headlining professional wrestler – before D — progressing onward to become a motion picture star – he is therefore E – the pre-Civil-Rights-Era prototype for Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

This is a clear instance where forcing this comparison between two superficially similar figures separated by at least four decades of in-ring activity does a disservice to both.

It simultaneously minimizes the significance of critical historical factors, negates familial influences, draws false equivalencies, and further overrates and underrates specific successes to sustain the arguments.

Absent the specifics of the era Strode was actively wrestling in, contextualizing any of his career activities – let alone isolating and dissecting his wrestling career – is a laborious chore.

The timeline of his activities lacks the tidy overlap of other athlete-wrestler-actors whose pursuits would follow similar but far more sterile trajectories in later years.

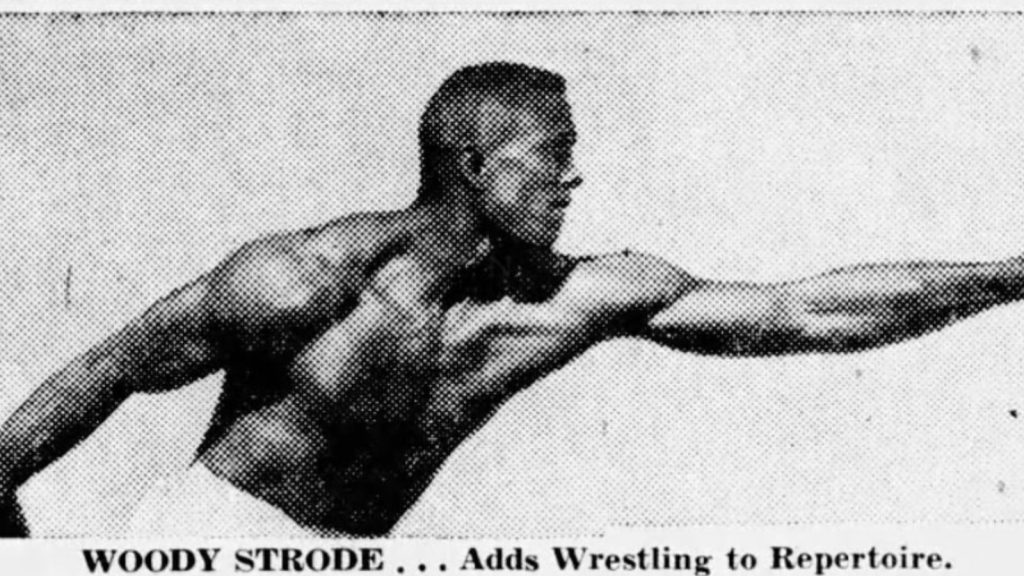

From the vantage point of wrestling fans, the relevant part of the story began when Strode made his in-ring debut in February of 1940. The Long Beach Press-Telegram advertised the event at the local Municipal Auditorium as such:

“Woody Strode, All-Coast end from UCLA, is making his first appearance in the local ring when he is matched against the rough and tough Lester Granes.”

Apparently, Strode’s world-class athleticism and coordination made up for whatever he lacked in experience.

Four days later, after Strode had cleared his first week of bouts, The San Bernardino County Sun described Strode’s destruction of Hank Mathenay as “one of the best matches on the card.”

“Woody Strode, who played end for the UCLA football eleven last season, flattened Hank Mathenay of Oregon with a series of flying body tackles and a body press in less than 17 minutes,”

described the reporter from The County Sun.

In all reality, Strode’s first foray into professional wrestling was a byproduct of a dearth of opportunities for Black football players of his era.

Strode had just concluded a star-making run alongside Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington in 1939 when they formed what was known as either the “Goal Dust Trio” or the “Gold Dust Trio” depending on which sportswriter was handling the story.

The three Black standouts led the UCLA Bruins to their first undefeated football season ever — albeit one with four ties.

Despite being a striking physical specimen whose size and skills would have placed him squarely in the upper echelon even amongst professional football players, the color barrier precluded the intermingling of Black football players with their White counterparts, thereby relegating Strode to matwork.

Along with testing the waters of pro wrestling, Strode’s proximity to Hollywood also afforded him the chance to try his hand at acting.

In June of 1941, it was reported that the Wagner studio production company had set a record of sorts when it packed a “special train” with “60 sepia film players” — a rather colorful reference to Black actors — and routed it toward Acoma, New Mexico to fill out the collection of extras in an African fort scene for the film Sundown.

“The group represented the largest number of sepia actors to ever go to such a great distance in the history of Hollywood film productions,”

wrote Lawrence F. Lamar.

“With the group went Kenny Washington and Woody Strode, members of that former great football passing combination at UCLA, who have been assigned small, but important bit roles.”

So it was that Strode, through the fulfillment of his uncredited role as a tribal policeman in Sundown, satisfied the bare minimum requirements of another rung on the elite trifecta of professional football, professional wrestling, and Hollywood acting.

In a practical sense, it was the best he could do at the time, and he accomplished all three feats within a three-year period.

By suiting up for the Hollywood Bears of the Pacific Coast Football League, Strode was competing at the highest level of professional football permitted by his complexion, and he contributed to the Bears 1941 undefeated PCFL championship team, along with his Goal Dust Trio teammate Kenny Washington.

Strode’s World War II Draft Registration Card

When World War II broke out, Strode officially enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps on October 16, 1942, and served until he was discharged on November 7, 1945, losing three years of potential gridiron, mat, and screen time in the process.

It was shortly following his military service discharge that Strode was included amongst the original crop of players who collectively broke the National Football League’s color barrier. This transpired in 1946 when Strode joined the Los Angeles Rams.

However, the incidents of racial discrimination in housing that Strode experienced during his NFL travels caused him to halt his LA Rams tenure after only one season.

“I never had been in the South and never had any problems in Los Angeles, so I didn’t have any scars on my memory,”

recalled Strode years later in an interview with Ralph Novak.

“I was a grown man before I knew what segregation was.”

Just a couple of years later, Strode found himself on the gridiron yet again, but this time more than 1,000 miles north of Los Angeles in frigid Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

That year, the Calgary Stampeders etched themselves in Canadian Football League history by completing a 12-0 regular season and winning the Grey Cup Championship. It remains the first and only undefeated title-winning season in CFL history.

It was only after he had already stamped himself as a Calgary Stampeders legend that Strode returned to professional wrestling in an off-season capacity similar to the sort that Wahoo McDaniel would emulate years later.

Despite being in his mid-30s and nine years older than he had been during his very first in-ring appearances, Strode’s recognizable name and immaculate physique made him an immediate special attraction in the Los Angeles market.

Strode would later explain to Bill Scott of The St.Joseph News-Press that he returned to pro wrestling after playing football in Calgary “to stay alive” after the coach had tried to transform him into a halfback.

In Strode’s own words, it was “murder up there” for halfbacks.

“In Canadian ball then, the running halfback was the big target,” explained Strode. “You had to get free on your own because the blocking just wasn’t there.

Every time you’d get about five yards, six gigantic defenders would hit you.

It got me in the legs after so long a time, and I knew if I was ever going to make a living I had to get out of that type of football.”

Strode made his triumphant return to the ring at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium in February of 1949 – after nearly a decade of ring inactivity – in a five-minute victory over Al Billings.

The Los Angeles Evening Citizen News referred to it as Strode’s “mat debut,” either not knowing or not caring about his brief flirtation with wrestling nine years prior.

As Woody began to mow down the mat competition in Southern California, his off-season activities were relayed back to football fans of Calgary in a positive light that categorized pro wrestling as more of a healthy conditioning method than a risky side gig.

“Woody Strode is keeping in shape for next season’s football with a spot of wrestling down California way,”

– reported sports editor Bob Mamami of The Calgary Herald.

“The long-striding Calgary Stampeder end appeared on a special event of a mat card at Olympia Auditorium and beat Rocca Toma before a crowd of 7,500.

Calgary’s football followers realized he knew most of the answers for gentlemanly conduct on the gridiron, but apparently, he also knows how to bounce an opponent on his noggin should the occasion arise.”

Meanwhile, Strode’s visage began to appear in many of the pro wrestling advertisements in the Los Angeles region, identifying him as a top attraction despite the fact that he was theoretically appearing on the undercard of events headlined by wrestlers like Lord Blears, Danny McShain, and Bobby Managoff.

A description of Strode’s match-ending sequence supplied by The Visalia Times-Delta in April of 1949 indicated that Strode hadn’t opted to alter his wrestling methods despite a decade of inactivity.

“Woody Strode, giant Negro football star, put up with Mel Petterson’s roughhouse tactics for 20 minutes before reverting to gridiron tactics for some 20 minutes and putting the blond lumberjack down and out with a series of flying tackles,”

reported the Times-Delta.

“The second fall came quickly as Strode bounced Petterson’s head on the mat and then flopped him for the three count.”

As Strode racked up wins, some folks in Canada seemed to be getting nervous about what wrestling success might mean for Strode’s football future and how that might prove to be a hindrance to the success of the Stampeders.

“Some people are wondering if Woody Strode, big Negro end with the Dominion champion Calgary Stampeders Football Club, will be on hand for the April 17 roll call when Coach Les Lear names his candidates for this year’s club,”

wrote Jack Sullivan.

“Woody has been wrestling professionally – at a reported $500-a-week price – in California during the winter.”

Stampeders fans probably had little to be concerned about, at least at that moment. With top CFL stars earning salaries in the realm of $15,000 per season, Strode would have needed to earn more than $400 every week for each of the 36 remaining weeks of the year that he wasn’t committed to the Stampeders simply to earn a sum that could compete with his annual football salary.

By the summer, wrestling fans in Los Angeles were all starkly aware that Strode — stripped of his pads and uniform — had one of the most impressive muscular physiques in all of wrestling.

A July edition of The Los Angeles Daily News published a daily workout attributed to Strode.

“On the days when he isn’t competing, Strode does 1,500 push-ups and 1,000 knee-bends,”

printed The Daily News.

“Takes him a good seven hours before he’s through.”

This workout seems rather far-fetched for two reasons. First, in light of what Strode would explicitly declare his workouts to consist of later on, it is unlikely that he performed this many push-ups on a daily basis.

Second, even if Strode had engaged in this many push-ups and knee-bends, it would certainly not have taken an athlete of his caliber and conditioning level seven hours to complete them all.

Strode’s reliance on football-themed shoulder tackles to put the finishing touches on his opponents was frequently reported, but Strode also demonstrated that he was competent in situations that called for classic grappling.

In his final Southern California match of 1949, Strode wrestled Sammy Menacker to a draw in what the reporter described as “the real match of wrestling skill” on that night’s card.

“Strode took the first go in 10:28 minutes with an arm lock while Menacker threw the Negro after a series of body slams that left the fans paralyzed along with the courageous colored boy. It was one of the cleanest wrestling matches ever witnessed.”

For all intents and purposes, Strode’s subsequent season with the Calgary Stampeders doubled as a part-time showcase for his wrestling talents.

In what many Stampeders fans probably considered an unnecessary distraction, even if it was a tremendous demonstration of Strode’s athletic gifts, the two-sport star would compete in football games on Saturdays, and then occasionally wrestle on Sundays.

On the weekend of his Canadian wrestling debut, Strode recovered a fumble to score a touchdown for the Stampeders against the Saskatchewan Roughriders on Saturday, September 19th, and on Sunday the 20th, he bested his wrestling opponent Tony Verdi in 18:01 “with three flying shoulder tackles and a spreadeagle press.”

Later, Edmonton Journal reporter Don Fleming reported that he had overheard an Edmonton Eskimos player suggesting that a deal ought to be struck with Strode’s wrestling opponent, Jerry Meeker, to render Strode a less viable threat during their forthcoming game.

“Maybe a broken arm would help,”

– the Eskimos player reportedly stated,

“but he’d probably catch those passes just as well with one hand.”

The Stampeders remained dominant during the 1949 campaign, although the team ultimately lost two games that season, with the second loss occurring at the hands of the Montreal Alouettes in the Grey Cup title game.

Regardless, Strode was once again named to the All-CFL first team, with wrestling enthusiasts in the area taking further note of his anatomical gifts.

“Woody Strode, the long-fingered end with a build that would rate at least a runner-up in a ‘Mr. America’ contest, has had 200 heavyweight wrestling bouts this last year around California,”

wrote Canadian Press staff writer Jack Sullivan.

“His record: 194 victories, six draws.”

Strode wrenches the neck of Jim Coffield

By the time February of 1950 rolled around, stories were circulating that alleged Strode might opt not to return to football due to a shoulder injury that he had suffered during the 1949 season.

However, the very next month, contradictory news reports confirmed that Strode had undergone a successful surgery and was about to make his return to the wrestling rings of California.

This was true, as Strode reemerged in the ring in April and was soon competing in tag team action alongside “The Black Panther” Jim Mitchell.

The press contended that the two were collectively “two of the Negro race’s most popular contributions to the mat profession.”

The next month, promoters Cal Eaton and Aileen Labell hosted “Woody Strode Night” at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, and presented a special trophy to “the tall, well-shaped bronze giant” who “took to wrestling like a duck to water, and in no time at all was easily one of the best-liked wrestlers performing.”

As the summer wore on, Strode was late to report to training camp, and the Canadian newspaper reported that the all-star end had received an attractive offer to become a full-time wrestler.

Stampeders coach Les Lears at least minimally confirmed that Strode’s pro wrestling obligations had prevented him from reporting to the team on time, stating in late August that he had spoken with Strode over the phone, and Strode said he would not be able to join the team until the time of their third game of the season.

“I told him that was no good, and if he wanted to make the team, he had to be here for the first road trip,”

Lear told The Calgary Herald.

Strode did eventually join his Stampeders teammates in late August, flying to Calgary right after an Ocean Park Arena bout against Bud Corby.

From there, he would fly back and forth between Calgary and Los Angeles for a time to fulfill as many of his contractual obligations as possible.

In the midst of Strode’s constant travels between Alberta and California, the Stampeders suffered through a disastrous 4-10 regular season after posting a combined regular-season record of 25-1 in the previous two years.

Woody departed from the Stampeders prior to the 1950 season’s conclusion with what was described as the aggravation of an old chest injury.

Stampeders coach Lester Lear would later refer to Strode’s malady as “an imaginary injury.” Lear was right to be suspicious; Strode returned to regular in-ring action within two months of his departure from Calgary.

In addition to facing fewer physical risks in the controlled confines of a wrestling ring, later interviews of Strode’s — like his 1984 interview with Allan Maki of The Calgary Herald — suggested that the frigid Alberta climate might have had something to do with Strode’s early exit for a warmer atmosphere in California.

“We trained hard, and we drank hard,”

stated Strode.

“We used to drink rum and scotch before practice just to stay warm. In fact, we used to have rum in our coffee at halftime. As we used to say, it was solely for medicinal purposes.”

It is at least equally likely that Strode was hopeful that a simultaneous revivification of his silver-screen career was in the offing.

After all, The Lion Hunters was already well into its filming by January of 1951, in anticipation of a March release.

A film talent scout had seen Strode in the ring, and thought the wrestler’s tall, muscular appearance rendered him a suitable fit for the role of Walu… as long as he shaved his head bald to complete the look.

“At first, I said no,”

Strode told a Chicago Tribune reporter in 1974.

“But then they told me the acting job would pay $500. For $500, I would’ve played Mickey Mouse!”

Now that Strode could generously be defined as a full-time wrestler, albeit one who clearly had his eyes on acting opportunities, he quickly had his undefeated wrestling record blemished by the (at least at that point) more accomplished actor-wrestler “The Swedish Angel” Tor Johnson.

From there, Strode began to absorb even more losses in Southern California before spending several months in Hawaii wrestling in the home state of his wife, legitimate Hawaiian Princess Luukialuana Kalaeloa.

In the summer of 1951, The Lion Hunters was released, and Strode received his first credited role in a Hollywood film. Additional roles would soon follow.

By January of 1952, he was busy filming Caribbean Gold in his role as a slave named Esau, who led an uprising against his masters.

Even though Strode seemed to be rapidly shifting his focus from the wrestling mat to the big screen, the extent to which he was respected by his Black peers was still quite evident.

When Black wrestling stars Jack “The Black Panther” Claybourne and Buddy Jackson prepared for a history-making clash in Atlanta for Claybourne’s world Negro heavyweight championship in April of 1952, Strode’s name was respectfully cited by Jackson on a list of the best Black wrestlers of the era.

After noting the recent passings of two Black legends – the original Rufus Jones and the first Reginald Siki – Jackson specifically added Don Blackmon, Seelie Samara, Frank James, Don Kindred, Jim Mitchell, and Woody Strode to his personal list of top active Black wrestlers in what could loosely be termed the pre-Bobo-Brazil era.

Outside of the ring, Strode continued to rack up film credits in films like African Treasure and Androcles and the Lion.

In the ring, he was still a special attraction, but his irregular appearances seemed to make him less essential to protect by way of keeping his loss column unblemished.

Yes, Strode certainly won more matches than he lost, but he frequently dropped contests to anoint other wrestlers as main eventers, like Warren Bockwinkel, and “The Zebra Kid” Billy Sandow.

In other locales, Woody Strode the wrestler was still hailed as a special attraction. When he triumphantly returned to wrestle in Calgary in 1953, Strode was hailed as a true star of the genre, billed as the Negro World Heavyweight Champion, and booked dominantly as a singles competitor.

He was also paired in a tag team combination with Bearcat Wright, and the two were collectively presumed by local reporters to have been the first Black tag team in the history of the territory.

Later in 1953, Strode filmed Gladiator alongside William Marshall, and when he made a media appearance in Oakland to discuss the film, Strode expressed his desire to the press that he wanted to wrestle in Northern California.

Writer Alan Ward immediately suggested that wrestling promoter Ad Santel book Strode to wrestle against Mike Mazurki, another wrestler-turned-actor who would later found the Cauliflower Alley Club.

Strode (right) battles Al Mills in Calgary

Strode’s ring appearance in Northern California never materialized, and he spent the remainder of 1953, all of 1954, and the bulk of 1955 focused on acting.

Strode’s return to pro wrestling in late 1955 was apparently born out of financial necessity, and a series of bad breaks connected with two of the mid-’50s Hollywood projects with which he was most directly connected.

“I had a seven-year contract to do the Mandrake films, but the series went broke,”

recalled Strode years later.

“Later, after I had done The Ten Commandments, Cecil B. Demille gave me his word that he would use me in at least one picture a year. Then he died. All the breaks seemed against me.”

Strode continued to intersperse movies with wrestling for the next few years. Even as he was gaining credit for appearing in credited roles in films like The 10 Commandments, in which he played the King of Ethiopia, Strode wrestled against the likes of Roy Shire and Primo Carnera.

All the while, Strode was hailed by several sportswriters as “the most outstanding Negro heavyweight to emerge on the mat scene since the heyday of Jack Claybourne.”

All signs indicated that Strode was attempting to permanently transition away from professional wrestling and into full-time acting as he approached his mid-40s, but he seemed reluctant to state these desires openly.

As he conversed with reporters on the set while Pork Chop Hill was being filmed in 1958, Strode tried to remain honest about his chances of retaining his financial viability in an unpredictable film-making climate.

“Don’t get me wrong; I don’t want to let my ego be lulled into a false sense of security,”

said Strode.

“This is a hard business — acting. Maybe the hardest of them all. I hope to be a good actor, like Jim Edwards, some day. If this role — this picture — hits, I’d love to do it. But I can’t say I’ll never go back to wrestling.”

If Strode was viewing wrestling as a necessary evil, 1960 was clearly the year that gave him serious hope that he would never be forced to indulge in it again.

Strode began the year in the title role of John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge, making Strode the first Black man cast in the leading role of a mainstream Western film.

When doing press interviews for the film, Strode credited much of his motion picture’s success — such that it was — to his extensive experience as a professional wrestler.

“After all, they’re both show business,”

– Strode told reporters.

A few months later, the epic film Spartacus was released, and in it, Strode portrayed an Ethiopian fighter named Draba.

When the smoke cleared, Strode was nominated for a Golden Glove award in the Best Supporting Actor category for his role in Spartacus, and he was now more recognizable to the general public as an actor than he was as a wrestler, at least on a national basis.

However, Strode would not reap commensurate financial rewards for several years. In the meantime, his conspicuous big-screen musculature enabled Strode to attract the sort of attention to himself that eluded most actors of his day.

When asked by Hollywood reporters how he maintained his head-to-toe strength, Strode provided a discernibly incomplete answer, seemingly attributing all of his results to the 200 push-ups he completed each day, in four sets of 50.

Nonetheless, this answer, straight from the horse’s mouth, was a far cry from the 1,500 daily push-ups Strode was alleged to have completed during his earliest days as a grappler.

Spartacus and Sergeant Rutledge worked wonders to present Strode as a viable actor, but it was his appearance on an episode of Rawhide — seen by 60 million viewers — that netted Strode his first carload of fan mail.

In a Pittsburgh Courier article, Strode conceded that he had returned to wrestling “to keep the wolf away from the door” in a financial sense, and hoped that his transition into Western films would enable him to branch out into other roles that would allow him to be presented as something other than a slave or an African native.

“I like the role of Comanche,”

– said Strode.

“It not only means I have gotten out of the jungle, but that casting directors feel I can do a greater number of roles effectively.”

Much to the chagrin of Strode, he would be required to return to wrestling briefly in 1962 for financial reasons at nearly 50 years of age.

Fortunately for him, Strode was in the midst of a film run that he would later credit with permanently transitioning him away from pro wrestling and into feature films.

“Papa [John] Ford took me under his wing,”

– explained Strode in his 1974 Chicago Tribune interview.

“‘Woody,’ he said to me, ‘I can’t make you a star, but I can make you a great character actor.’”

The film Strode appeared in for Ford that year was The Man who shot Liberty Valance. In tandem with Ford’s 1965 film Seven Women, those latter two films were credited by Strode as the movies that gave him the confidence to strike out on his own as a serious actor.

From there, Strode would eventually be cast in Shalako with Sean Connery and Brigitte Bardot, which opened up new horizons to him.

“I moved to Rome and really started making money for the first time,”

– said Strode in a Springfield News-Sun interview.

In another interview conducted by William Otterburn Hall in 1972, Strode elaborated on exactly how much he made after making Italy his filmmaking base of operations.

“I’ve made myself over a quarter million dollars in Italian Westerns in the last three years,”

– declared Strode, before directly linking the origin of his days spent entertaining people with his debut in professional wrestling.

“I didn’t plan my life to go the way it did, but here I am. I’ve been entertaining people for the last 30 years, one way or another.”

Worth noting is the fact that Strode never considered himself to be a bankable Hollywood star.

Instead, he directly credited his years spent in Italy with the most financially rewarding stage of his life, even if he felt the way he was cast in Italy was in service to maintaining the “white goody-guy image.”

“When I’m in Italy, they make me the bad guy,”

Strode told Associated Press reporter George Cole.

“The Italians like to be good people. But what the hell. I’m there to earn a dollar, and I’d rather be a villain on the world market anyway.”

Presumably, Strode meant that it was more financially rewarding for him to be cast as a villain on the world market than to be presented as a hero in the United States to limited acceptance.

Regardless, he was grateful for his opportunities, even if, as he told Ralph Novak, “If I were white for just six months, I’d be a multimillionaire.”

Still, Strode was evidently grateful to sit in the position that he occupied.

“I never get paid less than one thousand dollars a week, and I’m freer than all the white people in the acting business. I can work in London or Rome any time I want,”

– declared Strode to Vernon Scott of the UPI.

Then, without directly stating so, Strode seemed to lay part of the credit for his success upon a career that required him to repeatedly endure the impact of his body against a plywood mat, while upholding his physical strength and bankable appearance.

“You know why? Because I do my own fighting, roping, and riding in movies,”

– continued Strode.

“I don’t need doubles. And every morning I do 500 push-ups. Working is a way of life for me.”

By the time Strode ultimately passed away on December 31st of 1994, he had undoubtedly watched as at least one white wrestler catapulted himself into multimillionaire territory by way of a big-screen appearance that emphasized his chiseled muscles and downplayed his far-less-credible acting chops.

And as we all now know, there would be several more to come. Yet, based on every public statement Strode made while he was alive, it is unlikely that it would have bothered him very much.

He died as an incontestable success in three different fields of entertainment, and along the way, he had earned more money than he’d ever imagined could be possible.

Less than a year later, the film Toy Story would be released to great success and fanfare, and when a tiny sheriff doll named Woody… *ahem*… strode out onto the big screen, the filmmakers were very direct about the fact that the character was named as a tribute to a recently departed legend.

Nevertheless, the less obvious tribute was certainly unintended; every time someone pulled Woody’s strings, he always answered back, “Reach for the sky.” It was the essence of Woody Strode’s professional life across three disciplines, summarized in four words and preserved for all time.