Big Japan Pro Wrestling’s foundation appeared to be set as the founders were in place to ensure the company would do something no promotion in Japan could do better.

Big Japan Pro Wrestling – Start-Up 1995

On March 16th, 1995, 3,350 fans and media personnel filed into the Yokohama Bunka Gymnasium to witness Big Japan Pro Wrestling’s maiden voyage as a promotion.

The choice of date was a bold move, as both New Japan and Atsushi Onita’s FMW had events scheduled for the same day.

Meanwhile, 3,320 were in attendance at the Muroran City Gymnasium in Hokkaido to watch Onita’s FMW retirement tour, where Onita would team up with Mr. Gannosuke and Katsutoshi Niiyama to take on The Gladiator, Hideki Hosaka and Mr. Pogo in a street fight, making BJW the best attended professional wrestling show in Japan that night.

The show would be opened by The Great Kojika who thanked the fans for their attendance and said that everyone should have dreams no matter how radical the idea is.

The card for BJW’s start up event featured eight matches (as shown below) and while only the main event was set to feature weapons and general lawlessness, some of the other matches went purposely off script to help prepare the fans in attendance for what was to come.

Kishin Kawabata vs. Yuichi Taniguchi

Nam Ti Ryon & Kim Sopu vs. Seiji Yamakawa & Daisuke Taue

Takashi Okano vs. Yoshihiro Tajiri

Dani Dasota vs. Isao Takagi

Tony Norris vs. Mike Davis

Takashi Ishikawa vs. Hansan

Yoshiaki Yatsu vs. The Crypt Keeper

No Ropes Barbed Wire Tag Team Deathmatch: Shoji Nakamaki & Kendo Nagasaki vs. Ron Powers & The Iceman

The opening match saw the young Yuichi Taniguchi come up against Kishin Kawabata, who had been wrestling for just under four years at the time of the match.

Kawabata had debuted in late 1991 with SWS and would follow Sakurada to NOW and then to BJW, while Taniguchi had started training with NOW just before the promotion’s closure.

For the entirety of the match, Kawabata would deliver all of the offence to Taniguchi in a bid to show a clear difference in experience between the two and it finished in seven minutes and thirty-one seconds when Kawabata hit a running senton on Taniguchi and covered for a three count.

The tag team match that followed featured two rookies, Seiji Yamakawa who started training with NOW a year prior and Daisuke Taue who made his wrestling and IWA Japan debut just four months before BJW opened its doors, take on a pair of South Korean wrestlers.

The Japanese duo managed to isolate the less experienced member of the opposing team for most of the match, though Nam Ti Ryon and Kim Sopu would win in fourteen minutes and thirty-nine seconds when Daisuke Taue fell victim to a Samoan drop-pinning combination from his much larger opponent.

Former W*ING wrestler Takashi Okano, who competed under the name The Winger in the since-defunct promotion and later on in his career, took a detour to BJW from IWA Japan to face future fan favorite Yoshihiro Tajiri, who said he would bring a Mexican style of wrestling to BJW in hopes of picking up a win on his BJW debut.

Okano was flummoxed by Tajiri’s quick and athletic brand of offence, unable to do much to counter Tajiri’s moonsaults and other dives for a period.

Eventually, Okano managed to ground Tajiri, gain control of the match and pick up the victory in twelve minutes and fifty-three seconds after hitting Tajiri with a bridging German suplex.

Dani Dasota, who was known as Arashi during his time with Genichiro Tenryu’s WAR promotion and would later go by Daikokubo Benkei, vs. Isao Takagi, who had spent some time freelancing after departing All Japan in 1990 and would later pick up Dasota’s Arashi gimmick in WAR, was up next.

The match started with the two slugging it out in the ring but ended far from the confines of the ropes.

They would take their brawl into the crowd, all the way to the very end of the arena until the referee called a double count out after nine minutes and twenty-seven seconds.

Then came a short match between two gaijins. Mike Davis had competed across the NWA territories as one half of The Rock ‘n’ Roll RPM’s and one half of The Dirty Davis Brothers, though his opponent would become very well-known after his short stint in BJW.

Those not familiar with the name Tony Norris may instead recognise him by his name in the WWF, Ahmed Johnson. In four minutes and twenty-five seconds, Norris showed why the WWF touted him as a future star of their promotion.

He flew over the ropes, sprung up for impressive kicks, and finished Davis with two consecutive sit-out tiger drivers.

Takashi Ishikawa’s match with the South Korean Hansan kicked off with Ishikawa being thrown into various parts of the arena by his opponent’s entourage.

During the albeit short match, they frequently interfered with the former All Asia Tag Team champion. One minute and fifty-nine seconds later, Hansen tapped out to Ishikawa’s sharpshooter.

Only one match remained ahead of the main event; Yoshiaki Yatsu, who had worked everywhere from the WWF to New Japan, faced The Crypt Keeper, who was actually the Puerto Rican Jose Estrada Jr. in a mask made to resemble the character from Tales From The Crypt.

As silly as the character sounded, The Crypt Keeper had been billed as a serious heel across Japan in the early nineties and he would be treated no differently in BJW.

Yatsu would win via disqualification in seven minutes and five seconds after being jumped by allies of The Crypt Keeper in a match that the referee had already let enough slide by in.

A short interval followed to prepare the ring for the main event where the ropes would be removed and replaced with lengths of barbed wire.

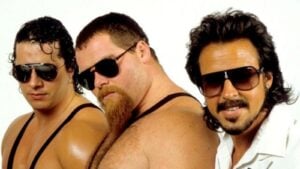

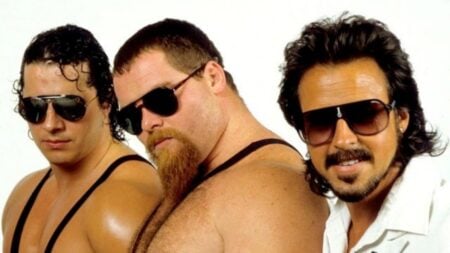

Entering first was the team of Ron Powers, who likely met Sakurada in his early days in WCW, and the masked Iceman, who was actually the former WWF, NWA and W*ING star Ricky Santana.

Sakurada and his partner entered the ring quickly, both dressed in white shirts and long pants which was a stark contrast to Ron Powers’ traditional wrestling gear and Iceman’s comic book villain attire.

Sakurada would wrestle as Kendo Nagasaki, the name that made him famous in the West, while his partner Shoji Nakamaki would use his usual name that he had used in FMW, W*ING and IWA Japan.

The match would only go for nine minutes and fifty seconds, but, like most deathmatches, the action in such a short span of time would be more than enough to satisfy the fans.

Powers and Nagasaki were the first to press against the barbed wire as they looked to wear each other down early on while the Iceman laid into Nakamaki with sets of steel chairs outside the ring.

Everyone then did a brawling lap of the arena until the latter pair made it back into the ring for Nakamaki to grind Iceman’s face against the barbed wire.

All four men would get the same treatment at one point or another in the match, causing each of them to bleed from the head before the Iceman was wrapped up in barbed wire by Nagasaki and pinned after a piledriver.

With the conclusion of the match came the end of BJW’s first night of action. The fans in Hokkaido seemed to be in high spirits throughout the show but came alive during the main event when the promotion’s biggest star Sakurada was in view.

It appeared as though Sakurada had finally started to receive the plaudits that he had sought throughout his career.

Crazy Matches

As BJW developed their style to distinguish themselves from other deathmatch promotions in Japan, their cards started to become filled with often bizarre match types that didn’t rely as much on the explosions that FMW were famed for or the standard trope weapons of deathmatches like barbed wire and light tubes.

One of the most popular was the ‘Crisis Big Born Deathmatch’ which at its core simply combined every conceivable deathmatch concept together in the same match.

The match kicks off on a scaffold positioned above a barbed wire net suspended over the ring. Surrounding the ring are various hazards: cacti, fire stones (electric space heaters wrapped in barbed wire), and dry ice.

Thumbtacks are scattered throughout the ring, while a tank filled with scorpions sits ominously at its centre.

The combatants are allowed to use an array of weapons, including light bulbs, light tubes, baseball bats, drills, buzzsaws, and swords. The match features all members of two teams actively fighting simultaneously under hardcore street fight rules.

Once every wrestler has fallen into the barbed wire net, the match transitions to its next phase, during which the net is removed.

Wrestlers can secure victory by submission, by having their opponent’s head held in the scorpion tank for ten seconds, or by causing their opponent to pass out.

BJW also have a habit of including live animals inside transparent caskets in their special deathmatches. A ‘Piranha Deathmatch’ sees barbed wire boards in the four corners of the ring while a tank full of piranhas sits in the centre.

Similarly, a ‘Scorpion Deathmatch’ uses the same premise, just with scorpions instead of piranhas and cacti instead of barbed wire boards. The aim of both matches was to hold an opponent in these tanks for around ten seconds.

Perhaps the most infamous version of one of these matches came as a follow up to a normal deathmatch between Shadow WX and Mitsuhiro Matsunaga, where the loser (Matsunaga) would have to face a crocodile in another deathmatch immediately after.

Given the size of the container, fans may have been expecting a full-sized crocodile but, as Matsunaga flipped the container, out came a baby crocodile.

Matsunaga didn’t look impressed and neither did the fans; so Matsunaga quickly grabbed the crocodile by its tail and flung it into the casket for the win.

A Bold Vision For The Future

Big Japan Pro Wrestling (BJW) emerged with a bold vision and an innovative approach that set it apart from other deathmatch promotions.

From its inception, BJW showcased a unique blend of brutality and creativity, evident in their match setups and the variety of weapons and hazards employed.

Their inaugural events were marked by an impressive level of organization and spectacle, capturing the attention of hardcore wrestling fans and critics alike.

Unlike many of their contemporaries, BJW demonstrated a commitment to pushing the boundaries of what deathmatch wrestling could be, both in terms of physical danger and storytelling.

The promotion’s capacity to integrate extreme violence with compelling narratives and diverse match types helped it carve out a distinctive place within the professional wrestling world.

This strategic differentiation not only highlighted BJW’s innovative spirit but also laid a strong foundation for its future growth and success.