We are familiar with the story of Jackie Robinson and the vital role that Branch Rickey played in the integration of America’s past time. In Memphis, Tennessee, however, Sputnik Monroe took Rickey’s insight to a greater degree by opening the door for African American performers and fans to integrate into the mainstream.

For this, Monroe deserves national hero status. His story needs to be told and his legacy underscored. It is an honor for me to do so. We travel back in time to mid 20th century. Our focus is on the American South. Race relations have been a considerable blemish in the landscape.

Despite landmark court rulings and a concerted Civil Rights campaign, African Americans were still treated as second-class citizens—changes in theory and principle but not in practice.

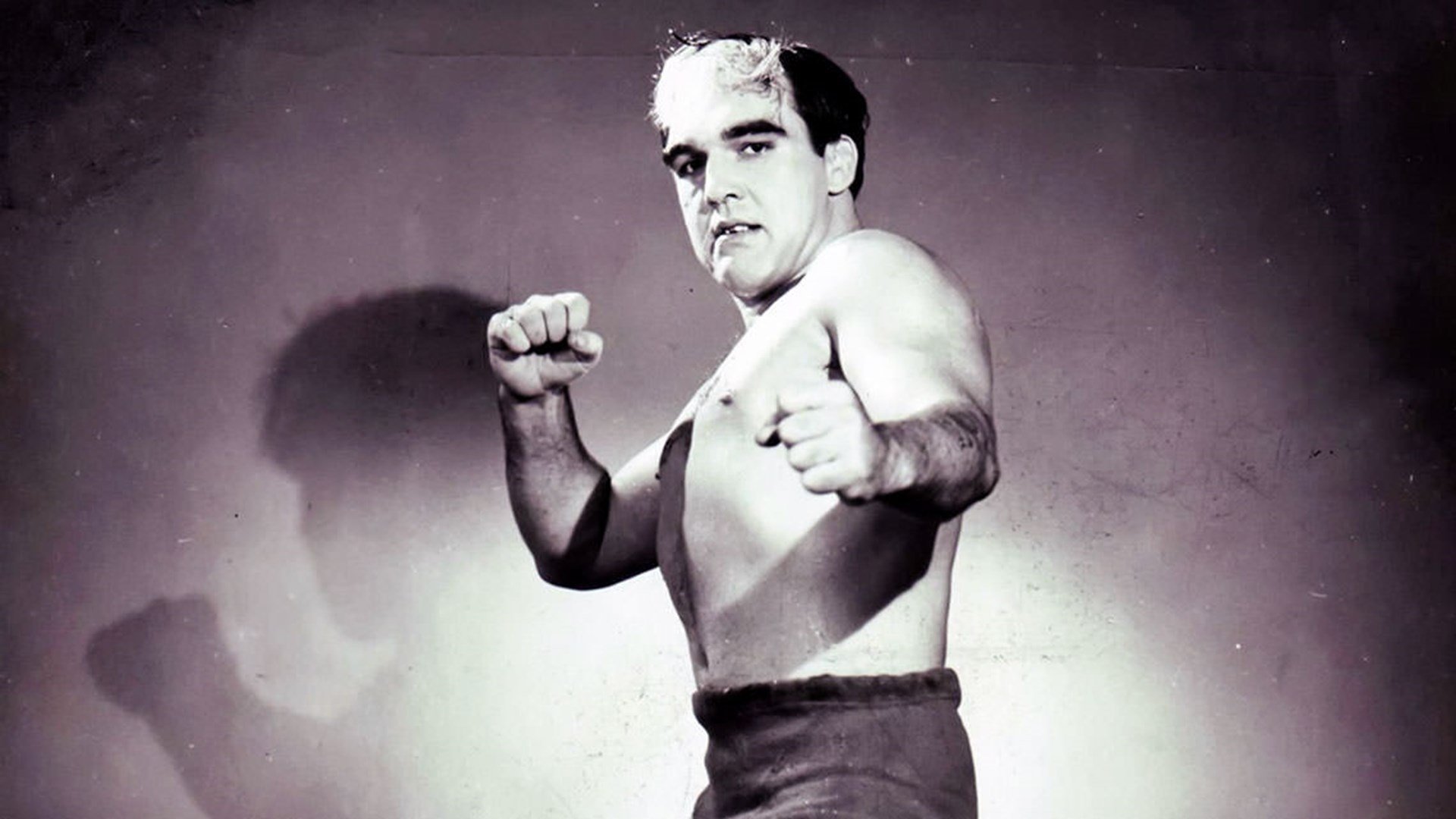

Sputnik Monroe | Civil Rights Crusader Extraordinaire

Nina Simone, the Jazz icon, summed the situation up very aptly in her 1964 composition Mississippi Goddamn “You don t have to live next to me, just give me my equality.”

The History Channel provided us with a clearer understanding of the picture in the following excerpt from their website;

The post-World War II era saw an increase in civil rights activities in the African American community, focusing on ensuring that Black citizens could vote. This ushered in the civil rights movement, resulting in the removal of Jim Crow laws.

In 1948 President Harry Truman ordered integration into the military. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that educational segregation was unconstitutional, ending the era of “separate-but-equal” education.

In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, which legally ended the segregation that Jim Crow laws had institutionalized. And in 1965, the Voting Rights Act halted efforts to keep minorities from voting. The Fair Housing Act of 1968, which ended discrimination in renting and selling homes, followed.

Or, referring once again to Nina Simone and her opus tune, That s just the trouble, too slow. Civil Rights became a mission for Roscoe Brumbaugh, a native of Dodge City born in December 1928. He broke into the business in 1945, appearing on many carnival shows.

It is interesting to note that in those pre-TV days, wrestling shows were often featured in carnivals before becoming enough of a draw to stage arena shows. He was billed as Rocky Monroe and then, as of 1957, Sputnik Monroe. Keep that year, 1957, in mind, by the way.

Brumbaugh was a pioneer heel who worked for the crowd like a maestro. He was very avant-garde in his promos. Circa 1950, he would refer to himself as twisted steel and sex appeal. ” Some 35 years later, when Scott Hall was morphing into a heel and abandoning his Big Scott Hall Magnum-like gimmick, he was billed as the Diamond Studd.

Studd had the Razor Ramon trademark toothpick and was introduced by his manager Diamond Dallas Page as twisted steel and sex appeal with the mandatory Dusty-like Mercy quote thrown in at the end.

Monroe might have been one of the first Caucasian performers to speak like an African American. This was made into an art form by the likes of Dusty Rhodes and Jimmy Valiant.

Monroe was wise enough to tap into the Cold War between the US and the USSR. Before championing the Civil Rights cause, he draws incredible heat by pretending to be a Communist.

As told to me by a Memphian I met in the course of my work activities, Monroe would rile the crowd beyond reason by using the Communist anthem, Die Internationale, and waving red flags. Nikolai Volkoff or Ivan Koloff decades before their time.

A very wise cousin of mine is convinced there is no such thing as coincidence. Driving home from a show in Alabama, Monroe had an excellent encounter that might prove my dear cousin right. In 1957, Spunik Monroe became tired while driving to a wrestling show in Alabama and invited a black hitchhiker he met at a gas station to take the wheel.

Upon arriving at the arena, Sputnik Monroe placed his arm around the man, which drew a chorus of boos and insults from the white crowd; in response to this, Monroe kissed the man on the cheek. Monroe would jump on this underlying racism as a promotional tactic and become a noteworthy figure in Memphis’s cultural history. He espoused and promoted a highly worthy cause while at the same time doing so to the benefit of the city’s promoters.

During a period where legal segregation was the norm at public events and during a general decline in the popularity of professional wrestling, Sputnik Monroe recognized that the segregated wrestling shows (whites sat in floor seats while African Americans were required to sit on the balcony) and were not correctly marketing to black fans.

In a stroke of genius combining social justice and the good old bottom line, Monroe realized he could champion his quest for civil rights while at the same time making it very lucrative for promoters to welcome crowds of fans from all segments of society. Total win, a win that they lured in support from all over.

Memphis had a 64 percent African American population. Its cultural hub was Beale Street, where African American patrons would flock to enjoy legendary blues performers such as B.B. King, Al Green, and so many more. Monroe broke down barriers by having the Moxy hang out on Beale street, make friends and at the same time talk up the wrestling shows he would be appearing in.

He would distribute tickets, adding a boost of polarizing energy to the shows. Monroe was the darling of the African American patrons while being scorned by the white patrons.

While the crowd was divided, the factions behaved properly. We can conclude that Monroe agreed with Oscar Wilde in thinking that the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about. He made an art form of being all out there to illicit a nice buzz from the crowd.

The witty, flamboyant Monroe began dressing up in a purple gown, carrying a diamond-tipped cane, and drinking in traditionally black bars in the black area of Memphis, where he would openly socialize with black patrons and hand out tickets to his wrestling shows. As a result of this, he was frequently arrested by police on a variety of vague, trumped-up charges, such as mopery.

Interestingly enough, Monroe was made to feel more than welcome on Beale Street. The only flack he drew was from certain segments of the city’s White minority. In each case, he would then hire a black attorney and appear in court, pay a small fine, and immediately resume the behavior that resulted in his prior arrests.

Like the legendary heavyweight pugilist Jack Johnson who was frequently arrested for crossing State lines with white women, Johnson would pay double the fine saying, “and this one, that s for the NEXT time.”

Due to this, and even though he was a heel at the time, his popularity soared among the Black community. He became a folk hero and staunch ally of a community long downtrodden on

At his shows, although floor seats in arenas would be half empty with white patrons, the balcony would be packed to capacity with black patrons, with many others unable to enter due to the balcony selling out. Monroe would refer to this section as the crow’s nest.

As Roger Daltrey sang, oh the change it had to come. The lower-level seats were no longer off-limits to the majority of the city’s population. Arenas were suddenly desegregated. The fans adored the spectacle, and the show’s organizers were delightedly counting the gate.

A friend of Monroe who was with him when they were stopped on the street by an African American man.

“We were walking down Beale Street, and a teenage black kid came up to us and said, ‘Sputnik Monroe.’ Sputnik answered, ‘You weren’t even born when I was here.’ The kid said, ‘My mom’s family has a picture of you on the wall.’ He said that they had a picture of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Sputnik Monroe, and Jesus Christ.”

Monroe was “woke,” while Southern Society was in de facto hibernation.

As he stated once, “I didn’t jump over walls, I broke them down.” While the change was slow to come, thanks to Monroe’s courage and innovation, the process was surely expedited. I can’t think of another wrestling personality who made such an impact outside of the squared circle. It is incumbent upon us to tell his story again and again to make sure his contributions are fully recognized.