For forty-two years, EMLL (Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre), later known as CMLL (Consejo Mundial De Lucha Libre), had ruled lucha libre in Mexico.

Not only did the promotion put on spectacular shows each and every week and have performers who had reached celebrity status within the country.

EMLL had impacted the culture of Mexico in such a way that every wrestling fan around the globe associates the country with the masked wrestlers and high flying that grew to become the standard inside of an EMLL ring.

However, as professional wrestling has proven time and time again, every star needs its rival and despite all of the odds being stacked against any potential rival to EMLL, one promotion found a way to make themselves a true alternative.

This new alternative has been known by many names, but it is perhaps most commonly known as the UWA (Universal Wrestling Association).

The UWA would overcome a seemingly insurmountable adversity to become the first real contender to the throne of Mexico’s top professional wrestling promotion since lucha libre began in the 1930s.

Despite the promotion’s relatively short twenty-year lifespan, it’s worth looking at the initial circumstances that made the UWA’s rise in 1975 so unthinkable yet so needed.

UWA –

The Issue of The National Wrestling Alliance

Professional wrestling is an ever-changing business and never had that fact been clearer than in the 1970s. Though interest in the artform had certainly declined in comparison to decades prior, the 1970s represented a time of change for the better and for the worse.

In every corner of the planet, new professional wrestling promotions emerged where other ones had failed and been forced to close their doors. Yet amongst all of this, it was perhaps in Mexico where this change was most unexpected.

To understand why this change was so unexpected in Mexico of all places, we have to understand the impact that the NWA (National Wrestling Alliance), the governing body that, for the most part, ruled professional wrestling in the United States.

They did this all throughout the fifties, all the way into the seventies, and had professional wrestling.

Only two pro-wrestling promotions provided a form of competition to the National Wrestling Alliance, one being Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association, which split from the NWA in 1960, and the other being Vincent J. McMahon’s Capitol Wrestling Corporation, which split from the NWA three years after.

Promotions that worked under the National Wrestling Alliance banner became known as territories of the National Wrestling Alliance.

This meant that the area (or territory) in which a promotion operated would be protected by the governing body of the National Wrestling Alliance so that the promotion could effectively own professional wrestling in that area.

For example, if someone wanted to start up a professional wrestling promotion in Dallas, Texas, where World Class Championship Wrestling (a National Wrestling Alliance member) was based.

It would be near impossible to be successful financially while the territory’s biggest stars were already being paid a wealthy sum by the existing promotion.

However, working under the National Wrestling Alliance banner in the United States did have its drawbacks.

The major disadvantage for professional wrestlers working under the banner was the fact that regardless of how many promotions joined the National Wrestling Alliance, there could only be one World Championship and one world champion.

This rule was the cause of Verne Gagne’s split from the banner as he felt he had all the qualities needed to be the World Champion, but the governing body did not believe he was a bigger draw for fans across the United States than then champion Lou Thesz was.

Vincent J. McMahon also pulled his promotion out of the National Wrestling Alliance partly due to his feeling that professional wrestling fans in his New York territory didn’t enjoy watching Lou Thesz.

The one-world champion rule was somewhat relaxed for foreign promotions that joined the National Wrestling Alliance, though their major championships were still promoted under the National Wrestling Alliance name.

This was the case in Mexico when their premier promotion, EMLL (Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre), joined the National Wrestling Alliance in 1953.

The Issue of Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre

Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre is a dynasty like no other when it comes to professional wrestling. Salvador Lutteroth (González) founded the promotion in September of 1933 following his service as both a lieutenant and captain during the Mexican Revolution.

Initially, Lutteroth was knocked back by larger venues in Mexico that were not entirely sold on the idea of professional wrestling like Lutteroth was when he spent time in the United States and watched professional wrestling for the first time.

September 21st, 1933 marked the date that Lutteroth would hold the first EMLL show in Mexico City at Arena Modelo.

Lutteroth would not encounter the issue of being without an arena to host his shows in again as he would soon acquire Arena Modelo and commission the construction of a larger arena to be built by 1943 – Arena Coliseo, which would hold up to 5,250 fans at a time.

No more than a decade later, Arena Coliseo would be too small to contain the masses of fans who wanted to see EMLL shows.

So, by 1956, Lutteroth built an even larger arena on the site of Arena Modelo, which had been converted into a professional wrestling school by Lutteroth. This new arena would be named Arena México and could seat up to 16,500 fans at a time.

Capturing the attention of thousands of Mexican citizens was no easy feat; yet Lutteroth was able to do so by crafting a distinguishable identity for his promotion like no other.

An identity that would encompass Mexican lucha libre as a whole for decades to come. Just a year after starting up the promotion, an American professional wrestler by the name of Corbin James Massey.

He made his debut for EMLL in front of thousands at Arena Modelo, though his attire featured something fans in Mexico hadn’t seen before in the ring – a mask.

The masked debutant Massey would work under the name La Maravilla Enmascarada, which translates roughly to ‘The Masked Marvel,’ to start what has since become a vital part of the lucha libre tradition, with countless Enmascarada (or masked wrestlers) donning masks of all colors, patterns, and themes.

Lucha libre isn’t just about flashy masks though and it never has been. Though a good mask can make for a nice image and sell a lot of merchandise, it was the lucha libre style of wrestling that made a promotion like EMLL stand out from the rest across the world.

Masked or not, when we think of a luchador we think of experts of acrobatics and technical masters, which is exactly what EMLL had and had continued to develop in abundance right the way through to the 1970s.

But how did those beyond Mexico come to know of these bold characters who could more often than not back their image up when the bell rung?

Even after the invention of the television, lucha libre was not broadcast outside of Mexico for some decades to come. That’s where the National Wrestling Alliance played their part.

Just as Lutteroth had visited the United States and witnessed the art that got him hooked on professional wrestling, foreign eyes soon caught glimpses of Mexico’s top luchadores.

With the introduction of the television came an opportunity for EMLL to expand their reach to the homes of Mexico and an opportunity for the National Wrestling Alliance to show off their stars and brand to Mexico as well.

The National Wrestling Alliance invited EMLL to become a member in 1953, making them the NWA representative territory for the entirety of Mexico as opposed to one specific region like in the United States.

EMLL were given the NWA World Light Heavyweight Championship to showcase on their shows in addition to the wide range of Mexican National Championships already established and sanctioned by Mexico City’s Boxing & Wrestling Commission (Comisión de Box y Lucha Libre Mexico).

The championship that EMLL received from the National Wrestling Alliance had been defended sparingly in the United States prior to its debut in Mexico where it would become a main feature for the promotion from 1958 onwards.

This led to EMLL rebranding their middleweight and welterweight championships to fit with the NWA branding also.

The relationship allowed the stars of EMLL to appear outside of Mexico with some amount of ease, provided that EMLL were content with them appearing elsewhere. This went both ways as stars from the United States and even Japan would appear on EMLL shows.

Perhaps the most important knock on effect from the NWA-EMLL relationship was what this meant for any fledgling lucha libre promotions in Mexico who one day hoped to reach the heights of EMLL.

With EMLL’s newfound international reach, television deals, arenas and training facilities, what aspiring young luchador would want to be anywhere else?

What fan would want to watch anyone but their favourite, larger than life star either at home or live at one of the arenas?

As if competing with EMLL didn’t already seem like an insurmountable task, the National Wrestling Alliance’s monopoly on professional wrestling expanding into lucha libre had just made it even more unlikely that Mexico would ever see a rival lucha libre promotion worth watching.

Still, where the impossible appeared to be just that, there were those who found cracks in what everyone thought to be the infallible machine that was the NWA-EMLL.

The Genesis of a Rival

With no prospect of an alternative to EMLL appearing in Mexico for the best part of forty years, there would need to be an exceptional reason for anyone to challenge the dynasty that Lutteroth had built.

This is more than a simple desire to see a different style of lucha libre or different stars pushed into the spotlight.

Any new promotion aiming to be a serious competitor in the industry would need a plethora of in-ring talent, a wealth of knowledge, and substantial financial backing, all of which would have to be near to the level of EMLL’s own. And yet, on one such occasion, the stars aligned to do just that.

The circumstances in which the Universal Wrestling Association came to be were the result of a key business decision made by the aging owner of EMLL, Salvador Lutteroth.

By 1974, Salvador Lutteroth had reached the age of 77 and had to start seriously considering what the future of EMLL would look like after his death.

Wishing to keep the business in the family, he announced that he would soon hand over the reins of the business to his son Salvador Lutteroth II, or ‘Chavo’ Lutteroth II, as he would become more commonly known.

This action did not go down well with many of the top stars in EMLL, though there were three stars in particular that took issue with the way Lutteroth II ran things while he was still learning under his father.

The first was Ray Mendoza, who at the time of the announcement was EMLL’s NWA World Light Heavyweight Champion. Mendoza was in his sixth reign with the championship, having captured it for the first time back in 1959.

And so had become synonymous with the title all over Mexico. Victories over the likes of Dory Dixon, Angel Blanco and even the South Korean-born star Kim Sung Ho at NWA’s Hollywood shows in California made Ray Mendoza into the luminary asset that he was to EMLL by the mid-seventies.

Mendoza’s main gripe with Lutteroth II was about how Chavo had little interest in pushing Mendoza’s sons – the Villanos. The issue itself was not new, Mendoza had talked to Salvador Lutteroth about moving his sons higher up the card and been knocked back.

But Mendoza’s positive relationship with the EMLL founder meant that he could rest assured that his sons would still feature at EMLL events and possibly move up the card in the future.

With new ownership looming, Mendoza’s uncertainty grew and he soon realised that his loyalty was to Salvador Lutteroth, not to EMLL.

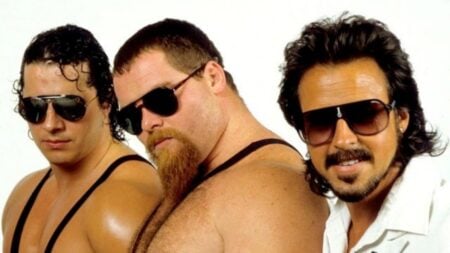

The second and third stars that had equally as big an issue with ‘Chavo’ Lutteroth II taking over in EMLL were René Guajardo and Karloff Lagarde. The pair were a tag team known as Los Rebeldes who even appeared in a string of lucha libre themed movies in the sixties.

They achieved this fame by being arguably the top rudo (heel/bad guy) tag team in Mexico in the late fifties and early sixties. Despite that, the pair also had glowing singles careers.

René Guajardo ended El Santo’s four year reign with the Mexican National Middleweight Championship, something most deemed unthinkable given El Santo’s icon status as perhaps the greatest tecnico (face/good guy) in Mexico at the time and perhaps ever.

Meanwhile Karloff Lagarde, the ‘King of the Welterweights,’ faced other lucha libre legends like Huracán Ramírez regularly and had a number of runs with NWA World Welterweight Championship.

Los Rebeldes had quite the friendship with Ray Mendoza; the three formed a trio in the ring after competing against each other in various luchas de apuestas (wager matches) in which they would all put their hair on the line as none of the three wore masks.

This friendship would earn EMLL the largest box office the promotion had ever seen on three separate occasions; trios matches against teams featuring El Santo, Rayo de Jalisco & Blue Demon along with a long-running feud with fellow rudos Los Espantos.

All contributed to EMLL’s financial success on the run up to 1974. As top stars and top ticket sellers, the trio would have been expected to have a greater say and influence backstage as well as in the ring.

One may be able to understand why Ray Mendoza was upset with both Lutteroths for not wishing to make stars out of his sons.

Unfortunately for EMLL and the Lutteroths, this friendship was so strong that Rey Mendoza and Los Rebeldes had developed a loyalty to one another that trumped any allegiance that the trio had to the Lutteroths.

Second to this, the trio also helped out a lot of the other EMLL talent with getting fairer pay for their performances and better conditions backstage.

The trio played rudos to the crowd but, in the eyes of the pro-wrestlers they worked with, they were invaluable influences to have around backstage.

The relationships that the trio had forged with the EMLL locker room and between themselves proved to be crucial in the coming months.

In July 1974, Ray Mendoza left EMLL and was stripped of the NWA World Light Heavyweight Championship, having held the title for seven months.

His conflicts with the Lutteroths and his disillusion with EMLL’s in-ring philosophy had become too great for him to continue with the promotion he had become a star of.

In the short-term, this was a blow for EMLL and their storytelling. Just a month prior to his departure, Ray Mendoza had successfully defended his championship against Alfonso Dantes during a feud with Dr. Wagner Jr. that was soon to reach a climax.

Though the Lutteroth’s likely did not expect the long-term impacts than Mendoza’s departure would have on their promotion.

Due to the NWA’s authority and EMLL’s overwhelming popularity in Mexico, even without Ray Mendoza, there was nowhere in his home country for Mendoza to wrestle on a regular basis.

He appeared at a number of irregular, small-time lucha libre events across Mexico for a short period after leaving EMLL but doing so long-term would not be viable financially as there was no way that those who ran these events could match Mendoza’s wages at EMLL.

An opportunity arose for Ray Mendoza towards the latter end of 1974 when he aligned with two other ambitious individuals hoping to create a haven away from the grip that the NWA and EMLL had over lucha libre in Mexico.

Francisco Flores and Carlos Máynez were the two that would work with Mendoza in an attempt to create the first real rival promotion to the EMLL in Mexico.

Flores had been a promoter in Pachuca since 1934 and offered a wealth of experience, and capital, to the group. Flores himself had ties to EMLL but he too grew frustrated with the product and the change of ownership was the final straw for him.

Flores’ nephew Máynez became Flores partner after Flores had already tried to have his daughter Esperanza amongst other family members work with him.

Despite being Flores’ fourth or fifth choice, Máynez had more than a keen interest in lucha libre having produced his own lucha libre show in Texcoco when he was just sixteen years old with materials he had been sent by his uncle Francisco.

This would set the scene for creation of a brand new lucha libre promotion in Mexico, with Francisco Flores and his right hand Carlos Máynez in charge of the business side of things and Ray Mendoza in charge of booking the events.

Flores decided upon the name ‘Promociones Mora’ after his late friend and fellow promoter Benjamin Mora Sr., though the name would soon become Lucha Libre Internacional and eventually the UWA (Universal Wrestling Association) by which the promotion will be referred to as from now on for the sake of simplicity.

The UWA name was originally adopted by fans as it was the term given to the group who oversaw operations within the promotion.

Under most circumstances, a new promotion starting up in Mexico wouldn’t impact EMLL in any serious way.

Other, short-lived, promotions had come and gone over the years, failing to pose any real threat to EMLL’s position as the true home of lucha libre.

However, the UWA started out with an advantage that other new promotions didn’t have and likely never could have had – stars from EMLL itself.

The Debut of the UWA

As expected, both René Guajardo and Karloff Lagarde jumped ship to the UWA and they brought with them a slew of both experienced and rookie luchadores to boot.

The likes of Dory Dixon, Suni War Cloud and El Vikingo had all departed EMLL for the UWA, as did Anibal, the then NWA World Middleweight Champion.

Of course, Mendoza’s sons, the Villanos, all joined up with their father in the new promotion where they would one day help to make famous the trios matches that became synonymous with the UWA, but even then they would not become as big a draw for fans as one other.

It may surprise people that the name that, in the long-term, drew the most fans to the UWA wasn’t Mil Mascaras, who worked both UWA and EMLL shows amongst others.

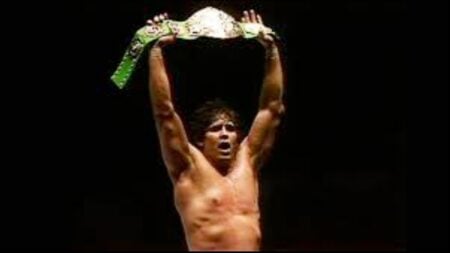

Instead, that honour went to a young man by the name of El Canek, who also featured on the UWA’s debut show. By the time that the UWA shut its doors in 1995, El Canek had held the UWA World Heavyweight Championship a record 13 times.

That being said, when the UWA held their first show in January of 1975 at Mexico City’s

Palacio de los Deportes, all eyes were on the major stars that had departed EMLL.

Roughly 21,000 people filed into the venue to see the card below, which vastly outshone the EMLL show taking place two days later on the Friday in terms of star quality.

Villano I vs. Atila

Dos Caras vs. Renato Torres

El Rayo de Jalisco & Tinieblas vs. Cesar Valentino & El Vikingo

El Solitario, Mil Mascaras & Ray Mendoza vs. Dory Dixon, El Canek & Suni War Cloud

NWA World Middleweight Championship Match:

Anibal (c) vs. Rene Guajardo

Something that may surprise you is that the NWA World Middleweight Championship was on the line in the main event, despite the UWA having no affiliation with the NWA nor an established relationship with EMLL.

This match also surprised both the NWA and EMLL, who had no idea that Anibal would make an unsanctioned defence of the title on the UWA’s debut show. Therefore, Anibal was quickly stripped of the belt by EMLL and he would not appear again for EMLL until 1982.

Even so, the UWA had achieved something that no other promotion in Mexico had achieved besides EMLL, pulling in fans in their drones to see stars that once wore the colours of EMLL battle it out with the next generation of lucha libre icons.

The Legacy of Change

Mendoza and his band of turncoats had made a significant dent in the ego of arguably the most respected promotion in professional wrestling’s great history.

They had shown that no matter how great in size and popularity a promotion was and regardless of its financial and global backing.

There would always be space for an alternative ready to take its place should they prove to match or even exceed what the progenitor is putting out for consumers.

Examples of this exist all throughout professional wrestling history, WCW, AEW, NOAH and many more created alternatives where an alternative didn’t seem possible.

This is also true of Lucha Libre AAA, whose formation would be the ultimate demise of the UWA who walked so that AAA could run.

Professional wrestling in Mexico owes much to Mendoza’s group, as does professional wrestling globally. It is likely that their success is the reason that fans have plenty of options when it comes to consuming lucha libre in the modern age.