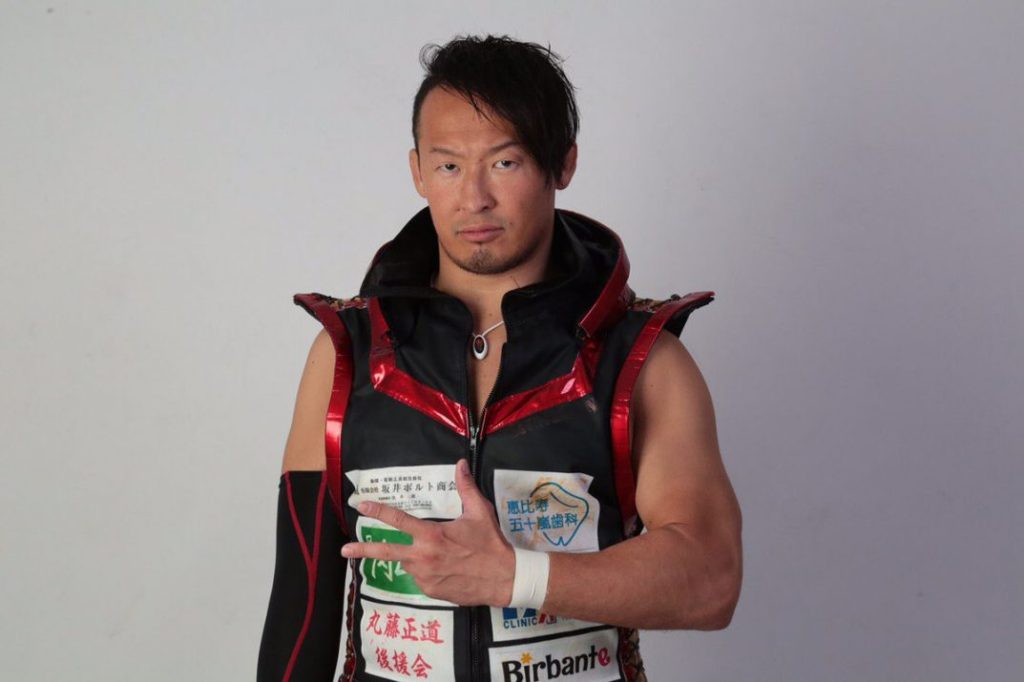

Naomichi Marufuji. Think of the first image that comes to mind when you hear the term ‘modern professional wrestling’. Is that image the sight of two wrestlers trading hard kicks back and forth while no-selling each other’s offense?

Is it daredevil acrobatics and blistering speed? Or maybe it’s insane high-spots and increasingly dangerous moves layered on top of each other? Whatever image you conjure up, one thing’s for certain: Naomichi Marufuji’s the one that popularized it.

He was so innovative and changed expectations so much, that people all over the world had no choice but to emulate what he did without giving him his much-deserved credit.

That’s why, for better or worse, Naomichi Marufuji is the progenitor of ‘modern professional’ wrestling.

__________________

Naomichi Marufuji – The Need To Adapt

Marufuji, who has become known as ‘Noah’s genius’ became this high-profile innovator out of necessity. He really started getting spotlighted at a time and in a place that was in dire need of creating new stars quickly.

Although he had debuted in All Japan Pro-Wrestling in August 1998, he didn’t do much wrestling beyond losing in prelim matches. He spent most of his AJPW time as his mentor Mitsuharu Misawa’s ‘gopher’, which was a fancy way of saying ‘lackey’.

When he wasn’t training, Marufuji had to basically get Misawa whatever he needed. He performed random tasks for Misawa and was often seen accompanying Misawa to the ring, clearing the hordes of screaming fans that extended their arms out to the Emerald Emperor.

And when Misawa left AJPW to form Pro Wrestling NOAH, Marufuji, as Misawa’s gopher/lackey/protégé/whatever, naturally followed him.

But NOAH’s early hears were mired in struggle. They had a very limited late-night TV slot, which made it hard for their program to really showcase new stars thoroughly. Then there was the fact that the new NOAH roster also had its issued.

Misawa was well past his prime and didn’t want to build the entire promotion around himself. Kenta Kobashi had to take over a year off due to how severe his knee injuries were.

Akira Taue was likewise well past his prime. The only person NOAH could reliably push as a potential new star was Jun Akiyama. And push him they did, as Akiyama pinned Misawa to become GHC Heacyweight Champion.

But where was Akiyama to go from there? Outside some outsider challengers, Akiyama had no worthwhile opponents to defend against, and therefore, no one to draw big crowds.

This Is Where Marufuji Came In

Marufuji had incredibly high expectations to deal with as Misawa’s direct protégé. And he also had to deal with the fact that he was small, standing at barely 5’9 and barely weighing 200 pounds. He was a good junior heavyweight, but that was about it.

And AJPW was always a heavyweight’s promotion, and many of the AJPW fans had followed over to NOAH with similar expectations and tastes.

So in order to adapt, Marufuji had to do something that would get fans’ attention and then keep it. So he looked back at what made his mentor Misawa so great and added that to the lucha libre style he had dabbled in to create a unique formula.

Thus was born Marufuji’s style, which has since been adopted by the overwhelming majority of top indy wrestlers to become famous in the United States since 2000.

What does a Naomichi Marufuji match look like?

A typical Marufuji big match can be summed up in the word ‘explosive’. Everything Marufuji did and does is done to elicit a surprise reaction. To make fans go ‘OOOOOHHH’ over and over again.

Not in a long and sustained segment of pure excitement, but in short bursts that build up, explode, die down, and then build up again.

Using what is widely considered the best match in Marufuji’s career, we can see what elements of Marufuji’s wrestling style have been copied time and again by others around the world.

The key elements of a Marufuji match, in no specific order, are:

- An opening sequence with lightning-quick chain grappling that leads to a stalemate and applause from the crowd

- Lots of dodging and ducking of big strikes, usually stomps or kicks

- Wrestler A works over a limb and maintains the advantage until Wrestler B gets a sudden counter and hits a strike hard enough to knock Wrestler A out of the ring

- Wrestler B would follow this with a dive through the ropes or some kind of springboard move

- Multiple stiff strike exchange, with the fans going ‘OOOHHH’ with each hit

- an insane ‘high-spot’ that involves incredible risk with potentially little reward done to excite the crowd, even if it means nothing in the context of the match’s story or logic

- Once the crowd is loud enough, the two wrestlers begin no-selling each other in extended back-and-forth sequences.

- An hour’s worth of big moves squeezed into much less time

-

And last but not least, one hundred or more thrust/super/side/savate kicks to the face in each match

Marufuji parlayed these elements of his wrestling style into considerable success. Despite being a junior heavyweight, Marufuji managed to win multiple junior heavyweight and heavyweight titles in NOAH and beyond. He is one of three wrestlers to win more than one super J Cup Tournaments.

He has won the junior heavyweight tag team championship in all three of Japan’s biggest promotions (AJPW, NOAH and NJPW). Marufuji has won both NOAH’s Global League Tournament and All Japan’s Champion Carnival. He is an eleven-time tag team champion across four promotions.

Three-Time GHC Heavyweight Champion

The reason that heavyweight title matters most is because he managed to break a barrier of sorts. Marufuji won a heavyweight’s title despite not being a heavyweight wrestler. But like Rey Mysterio, Marufuji used his maverick wrestling style to defeat heavyweight stars to become world champion.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that countless wrestlers have copied his style. They’re likely thinking that by doing so they would achieve success and fame like he did.

Like it or not, the overwhelming majority of today’s biggest stars owe their success to adopting Marufuji’s wrestling style. Guys like Seth Rollins, Low Ki, Austin Aries, Kenny Omega, Hiromu Takahashi, Will Ospreay, Bryan Danielson, the Young Bucks, and countless others have all copied, tribute or straight up ripped off what Marufuji did during his prime.

His work was especially influential in early Ring of Honor, which in turn influenced other indy federations like Combat Zone Wrestling and Pro Wrestling Guerilla. Which in turn influenced much smaller federations and local promotions all across North America and beyond.

Nowadays, it’s more common to see someone that looks and wrestles like Marufuji than it is to see a wrestler like Brock Lesnar, Goldberg, Big Van Vader, Ron Simmons or ‘Dr. Death’ Steve Williams.

That’s not to say such monster athletes don’t still exist; they still do. But for every one of them you’re likely to see twenty or more wrestlers who have adopted Marufuji’s wrestling style. Especially after his lengthy and high-profile wars with KENTA throughout the 2000s.

Naomichi Marufuji – A Catalyst For Change

Although the wrestling landscape was already changing by the time Marufuji reached his prime, he was nonetheless a catalyst in speeding up that change. The days of the immobile giants were long gone, and fan expectations regarding in-ring action changed as well.

It was no longer acceptable or financially viable for a wrestling match to feature two 300-pound hosses clobbering each other for ten minutes and the match ending in a big splash.

Once WWE won, the Monday Night Wars ended, and the many fans that were there just for the ride had gone, and only the die-hard fans remained; there was a demand from large groups of fans for things to go back to being less about wacky angles and ‘crash TV’-style swerves and back to grappling.

And as Chris Benoit and Eddy Guerrero’s celebration at WrestleMania XX demonstrated, the age of the smaller wrestler had arrived. And Naomichi Marufuji was to Japan and the independent scene what Benoit and Eddy were to the biggest wrestling company in the world.

Whether his influence on pro wrestling is/has been good or bad is entirely up to opinion.